This is an article that Dr. Jonas wrote for the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM), a Christian non-profit organization based in London. The founder and spiritual guide of this world-wide contemplative community is the Roman Catholic (Benedictine) priest, Fr. Laurence Freeman. Fr. Laurence is a good friend of the Tibetan Buddhist Dalai Lama. After His Holiness the Dalai Lama co-led WCCM’s tenth annual retreat–the John Main Seminar in 1994–his reflections on Christian scripture were published as a book, “The Good Heart” (Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1996).

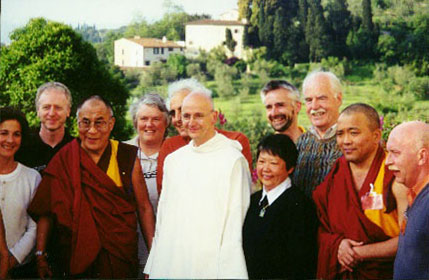

Together, Fr. Freeman and His Holiness created a series of Christian-Buddhist dialogues called The Way of Peace. I was fortunate to attend these meetings–Bodh Gaya, India in December, 1998, Florence, Italy in May, 1999 and Belfast, Northern Ireland in October, 2000. This article is a short reflection on the events in Bodh Gaya and Italy.

image © Robert Jonas

As an American contemplative Christian I am grateful to have been included as a participant in the Ways to Peace pilgrimages to India, Florence and Northern Ireland. I grew up Lutheran in the 1950’s, in a denomination that had effectively repressed its contemplative heritage when it severed its connection with Rome during the Reformation. Through the gateway of zazen and Taoist meditation (as a Dartmouth undergraduate in the late 60’s), I found out that just sitting and doing nothing could be, in the spiritual dimension, doing something. This was a startling revelation for a Midwestern Green Bay Packer fan, working class guy like me who had always been taught that being non-productive, even for a moment, was sloth, a shameful sin.

With the help of writers Thomas Merton, Alan Watts, and D.T. Suzuki, I gradually realized that perhaps meditation could also be a bone fide Christian experience. It was St. John of the Cross who finally escorted me across the threshold into the mainstream of the Catholic mystical tradition. It was St. John who taught me that “emptiness” can indeed be a kind of Zen spaciousness, but also a living dimension of Presence in which God is the doctoral witness who is always purifying my mind and heart (if I am willing to let the Spirit take the wheel). Under the tutelage of some counter-cultural Carmelite monks in New Hampshire, I had joined the Catholic Church and became a Third Order Carmelite in 1973.

Since the 1960’s I have followed Christ into the blossoming fields of the Buddhist-Christian dialogue. After finishing my doctorate in psychology and education at Harvard, and after several years as a psychotherapist and organizational counselor, I completed a post-doc Master’s in spirituality at the Weston Jesuit School of Theology. My thesis was entitled, “A Perfect Storm of Healing: Christian contemplative prayer, Buddhist meditation, and psychodynamic psychotherapy.” In 1994 I founded a lay Christian contemplative community called the Empty Bell in Watertown, Massachusetts. Our core mission was to bring Christians and Buddhists together. I have taken part in many interfaith dialogues over the years. In the 1970’s and 80’s most of these dialogues were between Japanese Zen Masters and scholars and Roman Catholic theologians, monks and nuns. However, in the last decades, the audience has become more discerning and more diverse.

Today, many more Protestants and lay people are involved in interfaith meditation and sharing. Many Americans who grew up Christian have flocked to the work of Vipasyana (Insight Meditation) Buddhist teachers Joseph Goldstein (Insight Meditation and Seeking the Heart of Wisdom), Sharon Salzberg (Loving-Kindness) and Jack Kornfield (A Path With Heart) and to the popular work of Tibetan Buddhists Chogyam Trungpa (Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism), Pema Chodron (Start Where You Are, and The Wisdom of No Escape) and the Dalai Lama (The Art of Happiness and The Meaning of Life). In America, many Buddhist teachers grew up in Jewish or Christian households, and then left their own traditions to become Buddhist. But increasingly, both Jewish and Christian adults realize that they can integrate Buddhist insights into their own spiritual life.

Of all the Buddhist traditions (and there are many), it is the Tibetans who have most actively reached out to Christians–in part because their practice includes a devotional dimension. The Dalai Lama told us that while he is in dialogue with all the great world religions, he cherishes a special relationship with Christians. Though Tibetan Buddhists do not believe in the Christian God, they seem more friendly to the devotional sensibility of Christians, and in their Tibetan tantric practices–more inclined to see the fundamental importance of the I-Thou encounter. Like us Christians, the Tibetans sense a deep relationality in their “emptiness,” a relationally that the Zen teacher Thich Nhat Hanh called “interbeing.”

Throughout the Way of Peace in India, Italy, and Belfast, I thought that Fr. Laurence Freeman and the Dalai Lama were ideal representatives of their different religions. They are smart, educated and well-informed, sincerely disciplined in their practices of meditation and prayer, and, perhaps most importantly, generous and kindly toward one another. Both seem happy in one another’s company. Both men can stretch their arms wide enough to hold with compassion and patience the incredible diversity within their own communities. They both manifest a gracious humility about their work and their views.

Our sojourn in Italy was blessed. I will always remember the moment when His Holiness the Dalai Lama was leaving our place of dialogue outside Florence, the Villa Saint Leonardo Al Palco, a Benedictine “Opere Ritiri Spiritual,” to give a talk in in the city itself. As he descended the stone stairs in the orangeing light of late afternoon, a group of about 20 European admirers waited breathlessly for him near the edge of the parking lot. In front of him, behind him and beside him walked armed Italian police and above us hovered a blue and white police helicopter. One young European woman in the group stood out for me. As the Dalai Lama approached she bent forward, smiling broadly. She shuffled forward into his path, holding out a white scarf. As he approached her with his palms pressed together in greeting to the group, the woman looked up at him with such intensity that her eyes might have popped out of her head. On her face I saw a fluid, complex mix of emotion–hope, fear, love, reverence, and so much longing–perhaps to touch His Holiness, perhaps to be blessed or healed by him. Her need seemed so great that, in embarrassment for her I averted my eyes. She seemed too far outside herself, perhaps wanting more from this man, Tendzin Gyatso (the Dalai Lama), than he could possibly deliver. I thought of the messianic political expectations that, in a time of great despair, were put upon Jesus. Indeed, the power of the Holy Spirit, Jesus himself became a doorway to God, who he said was greater than him. But as we’ve learned over the centuries, even Jesus can be idealized in a way that prevents his followers from realizing their own complete gifts of the Spirit. Jesus’s message, especially in the Gospel of John, was to wash our feet, be our friend, and to share everything that he had with us. Christ-in-us gives away the special, higher place. Many ethnic Tibetans and Euro-American Tibetan Buddhists believe that this man Tendzin Gyatso, is a god, though he himself tells us with a compassionate smile, “I am only a simple monk.” Still, I wondered how one person, being the recipient of such fervent devotion, idealization and projection, can remained centered.

In this moment, on the steps of our monastery, I saw how the Dalai Lama’s behavior is so completely congruent with his statements about himself, and his view of reality. One gets a sense that sees carefully and accurately the particular suffering of others, and yet he always sees to still another depth, to the origin of the person’s subjectivity. And in each person’s depths, no matter how wounded he or she is, he sees the Buddha-nature waiting to be born. And that is what he bows to in each person: the embodied person and personality, and yet simultaneously, the One in the one. I watched as His Holiness paused to be with the group on the terrace. His bodyguards and the many police waited and watched with some anxiety.

I’m sure that in each person’s eyes, His Holiness saw the hope and wisdom of the Buddha because that is where he sees from. So, even now, though he was already late for his address to thousands of people in the city, an engagement packed into a strenuous schedule with us, and between an exhausting trip to England and another approaching trip to Munich, the Dalai Lama lingered, bowing to each person and to the woman, and then exchanging the traditional greeting of the white scarves. I thought, “What a simple, gracious human being!”

When asked what is the source of his happiness and wisdom His Holiness replies that it is entirely due to the practices of meditation that are the gift of his tradition. Each morning he arises before dawn to meditate and to pray, and he finds additional quiet times each day. But in a way, he is always meditating, very much in the flow of what we Christians would call “unceasing prayer.” One morning, after accompanying His Holiness to Florence for a public talk, Fr. Laurence told us that when His Holiness finally joined him in the waiting limousine after walking slowly through a gauntlet of admiring, clapping and crying Florentines, he immediately began to pray. And that is how he stays focused in his heart. All his experience must come through the heart of prayer, through Buddha’s desire for the liberation of all beings from the bonds of suffering, illusion, attachment and ignorance.

In his humanness, the Dalai Lama has his own teachers to whom he feels responsible. One of them is the great Buddhist teacher and hermit, Milarepa. Once His Holiness told the story of how Milarepa was so unattached to fame that he wanted to die unknown in a cave. “But,” he added, “I am not as perfect as Milarepa. I will get a gold watch.” In the presence of His Holiness, Tendzin Gyatso, no one can take him or oneself too seriously.

In India, when someone in our group asked His Holiness why the Tibetans seem so happy while most Christian ministers and priests seem so dour, His Holiness, who doubtless has observed the same fact, graciously shifted the spotlight to such differences within his own Buddhist community. But later, when comic relief was needed again, Fr. Freeman offered his response with a smile, saying, “I want to come back to the question about the stiffness of Christian leaders [evoking much laughter in the room]. Just to disprove the theory, I will tell a joke. It’s about Pope John XXIII in the early 1960’s. A reporter asked him, ‘How many people work in the Vatican?’ And he answered, “About 10%”. Always, in India (in the shadow of China and its occupied Tibetan territory) and in Florence (almost within sight of the vapor trails of the NATO jets attacking Milosevic’s army in nearby Serbia) our critically important talks went on in an atmosphere of good humor.

Of course, the dialogues touched upon many serious teachings of spiritual practice from the Buddhist and Christian traditions. We discussed the differing roles of icons, the imagination, and of scripture in each tradition. We spent many fascinating moments lingering on subtle linguistic distinctions, such as the true nature of Buddhist and Christian “emptiness”. But I think that both leaders and most of the participants came to emphasize the importance of acting with compassion in each moment toward oneself, others, and all sentient beings in creation. There was general agreement that merely adhering to dogmatic statements of faith in either tradition is, in itself, not an authentic spirituality. Nor is having the “correct” theology sufficient. Buddha, Jesus and the great teachers in both traditions hope that we will become something and live something, not merely think something or feel something.

Both Fr. Freeman and the Dalai Lama emphasized how important it is to have a daily practice of meditation, a practical way to discipline our unruly minds. As a Christian who is familiar with Jesus’ many admonitions to love and to have compassion, I was particularly struck by the Dalai Lama’s detailed observations of compassion. He said that there are three parts to compassion:

- Intending to attain perfection and enlightenment for the benefit of others.

- Opening to genuine empathy and connectedness to others, even our enemies.

- Seeking and acquiring a good, sound intellectual understanding of suffering.

His Holiness, in characteristic humility, shared how even after his many years of commitment and practice, he is still learning the depths of these dimensions of compassion. Fr. Laurence appreciated His Holiness’s comments, not only for having learned some facts about Buddhist practice, but also for hearing such a deep resonance with the teachings of Jesus. We too seek the compassion of Christ and his self-emptying for others. We too seek Christ’s presence in relationship with our enemies. And we too seek to integrate an intellectual understanding of scripture and other holy teachings in our tradition with the open-heartedness that Jesus manifested and taught.

Fr. Laurence and the Dalai Lama go forward in this Buddhist-Christian dialogue with the understanding that they are not trying to convert one another. They are simply doing what friends do, sharing with one another what is most important to each, not wanting anything from the other. Fr. Laurence stands firm in his Christian faith, and the Dalai Lama told us clearly, “I do not want to become a Christian.” They exemplified for me a very powerful and precious model of how one might completely open one’s mind and heart to someone very different, all the while not losing one’s own self, vision and commitments. There is in both men a capacity to listen deeply to the other without pre-judgment, and to let some new truth emerge, while at the same to know his own identity and mission in life. This is an extremely subtle and mature skill, a way of being that calls each of us to a higher standard of love, wisdom and compassion.

As a psychologist I can say that this high standard may not be attainable by everyone. One must have roots within one’s self, and indeed possess a self before one can throw the self’s doors open to others, and to the Divine Other who is within us and all everywhere. Perhaps many people in this world are too wounded to appreciate the depth of compassionate surrender that the Dalai Lama and Fr. Freeman practice and advocate. Many of us have fragile egos and fearful, hardened hearts that cannot often tolerate this level of openness. Still, I believe that the way of love is attainable in a suffering, often violent world. Certainly, those of us who feel drawn to deeper disciplines of the mind and heart can learn from Buddha and Jesus and the masters in their respective traditions. But there seemed to be agreement that even the most powerful spiritual disciplines cannot be practiced in isolation within ourselves or even within our own communities. Because more and more of our local problems are global problems, we must create communities of presence and compassion that transcend the boundaries of our unique, inherited religious faiths. The Way of Peace has offered me some hints of how this might be possible. Thank you.

© Robert A. Jonas, 1999-2023 (reprint by written permission only)