In October, 2000 an unnaturally large orange and yellow sun, veiled by thin gray clouds, rose up over the Irish sea as my friend Colum Kenny and I sat watching from our seats on the Dublin to Belfast train. Speeding along the coast of the Irish Sea, I noticed with dismay that beautiful farmland was being cleared for housing developments. I asked Colum about it. “Since the Good Friday Peace Accord two years ago, the pace of economic development has picked up, especially in the Republic of Ireland. There’s no unemployment. We’ve never had such prosperity. They call it the Celtic Tiger. But still, the peace is fragile. Maybe the Dalai Lama can have some influence here. We’ll see.”

Colum is a journalist and professor who lives with his wife, Cathryn, and three boys near Dublin. He is a tall, handsome man with an encyclopedic knowledge of Irish politics, poetry and history. Colum is also a Christian meditator who, like me, was excited about the Buddhist-Christian dialogue. We had been on two prior Buddhist-Christian retreats together with the Dalai Lama and Fr. Laurence Freeman, a Benedictine monk. As our interfaith leaders, they had called the series of meetings, in India, Italy and Belfast, Northern Ireland, “The Way of Peace.” We were headed to the final Way of Peace meeting. This one would be on a bigger scale than our previous two gatherings. Instead of a small band of forty to seventy pilgrims, we expected almost seven hundred people at some of the Belfast events.

As in India and Italy, Fr. Laurence had asked if I would play the shakuhachi for some periods of meditation in Belfast. I said yes because I liked Fr. Laurence personally, and because I was committed to his vision of friendship between Buddhists and Christians. With so much inter-religious violence in the world, it seemed important to reach out and make friends across traditions. And, having been involved in interfaith dialogues and retreats for fifteen years, I’d come to the conclusion that Fr. Laurence was one of the most sincere, smart and theologically astute leaders of Buddhist-Christian dialogue in the world. As a close friend of the Dalai Lama, Fr. Laurence was uniquely situated to lead the discussions.

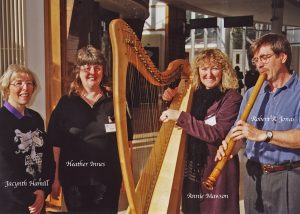

I had come to this third Way of Peace gathering because I wanted to learn from Fr. Laurence about the Christian contemplative path, and about how to engage in dialogue with Buddhists. I also wanted to make a contribution to interfaith dialogue here in Belfast, Northern Ireland myself, where there had been so much bloodshed between Protestants and Catholics, especially in the last thirty years. I would play the shakuhachi with other Celtic musicians, such as Jacynth Hamill, Heather Innes, and Annie Mawson (see pic), and I would offer a workshop on contemplative music as well.

Just before leaving home I had spoken with one of the Way of Peace leaders at the sponsoring headquarters in London, the World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM). He had said that the preliminary sign-ups showed that I would have at least twenty-five people at my workshop at Belfast’s Waterfront Conference Center. I entitled the workshop “ Meditation, Music and Metanoia.” Metanoia, from the Greek, meant a change of consciousness or a change of heart. I knew that Blowing Zen was changing me, but I still didn’t know how to describe the changes. Maybe teaching about my spiritual practice of Sui-Zen would help me to find words that would be helpful to others.

I hoped to encourage others to explore the powerful role of music in personal and social change. As part of the course description I wrote that I would “play several ancient honkyoku, share stories and poetry from this unique Buddhist-Christian ministry, and lead us in discussion of how we use silence and music to ground ourselves in our work for justice and reconciliation.” I didn’t have a lot of self-confidence about this. None of my shakuhachi teachers had ever talked about linking Sui-Zen to social justice. I had heard of only one person who explored this dimension of the shakuhachi every day. One of my friends, Monty Levenson, made and sold shakuhachis, and shakuhachi CD’s. Just before leaving America Monty had forwarded letters to me from a prisoner in a Federal Penitentiary, Veronza Bowers, Jr. (aka #35316-136) who used the shakuhachi in a prison healing ministry. In one letter Veronza wrote about a time when he was sitting in the prison yard with the shakuhachi to his lips, just as another young prisoner named Punchy rolled past him in a wheelchair. Veronza knew that Punchy had been shot in the back and paralyzed from the waist down. He told me that as he watched and blew down the bamboo, his shakuhachi “began to cry”.

Sitting next to Colum on the train was an opportunity for me to learn about Ireland. We sipped coffee as we gazed out the train’s windows.

“O.K., Colum,” I confessed. “I’m at a real basic level of knowledge about Ireland. What’s ‘the Republic’, and who is fighting whom?”

Colum turned toward me, picked up his cup and leaned back against the window. “We are now in the Republic of Ireland, a sovereign country. We’re 90% Catholic, that is, Irish Roman Catholic, not just Roman Catholic.” He smiles. “There’s a difference, you see.”

“Northern Ireland is something different. It was created in 1921, and it’s 60% Protestant. Historically, the Protestants have come from and are still loyal to England. So they call themselves Loyalists. They parade the British flag, holding up the Queen as their sovereign, even more vehemently sometimes than the British themselves. Northern Ireland is part of the British Commonwealth, like Scotland and Canada. The Republic, in the south, is mostly Catholic and a lot of the street signs are still in the ancient Gaelic language, to emphasize the separation from English-speaking, Protestant people.

“The enmity between Protestants and Catholics is long-standing, centuries old. Neighborhoods and service organizations are usually divided among the two groups. Schools throughout north and south are either Protestant or Catholic, rarely both. Catholics are a minority in Northern Ireland. Protestants have the political and military power there. So, of course, the Catholics feel oppressed. Over the years some of them have turned to the Irish Republican Army, the IRA, and its political wing, Sinn Fein, to assert their rights, sometimes with violence.”

“Do you see a solution?”

“I don’t know. Cathryn and I have always had our sons in mixed schools, Protestant and Catholic. That’s been our hope, that eventually we’ll see a reconciliation between the two groups. But it is very difficult. The hatred goes so deep.

“The Catholics in the south see themselves as the original inhabitants, and they want the British out of Ireland altogether. They want a united Ireland, north and south. Passions about these different visions of Ireland—the Loyalist and the IRA– have led to much bloodshed. Since the late 1960’s the periodic eruptions of violence between Protestants and Catholics have been called The Troubles.

Even though The Troubles are officially over with the signing of the recent peace accord, tension remains. We might feel it in Belfast. Much of the violence has happened there.”

Ahead of us, along the track is a big green sign that reads, “Portadown”, a town that straddles north and south. We’ll now travel into Northern Ireland.

When Colum and I had changed trains in Dublin that morning, we were told that someone had just called in a bomb threat for the Northern Ireland side of the rail line. The train would have to stop here, and everyone will have to get off. We’ll have to take a bus into Belfast.

Colum leans over and points outside, “See all those flags fluttering from the electricity poles? They’re loyalist flags (loyal to Britain), claiming this as their territory.”

“It’s a provocation, then?”

“In part, sure,” Colum answers. “Every July 12th, the Loyalist Orangemen come out here to Portadown to celebrate the British victory at the Battle of the Boyne. Of course, the Irish nationalists take it as a provocation and try to stop them. It’s always a near-violent situation.”

As we climb down from our train and walk toward the row of waiting two-decker buses for the trip into central Belfast, Colum touches my shoulder. Walking just ahead of us is a little old man in black clerical garb pulling his luggage on wheels. “I know that man,” Colum says. “He is Cardinal Cathal Daly, Ireland’s only cardinal and the retired ‘Primate of All Ireland’. What an intense life he’s had. He’s retired in Belfast now. But he was born in 1917 and participated in Vatican II. And, if he’s alive, he’ll vote for the next Pope.”

“A brave man, a Catholic living in Belfast?”

“Well, yes. In some areas of the city, you’ve got to be brave, no matter what you believe. The Dalai Lama is brave, asking to bring Protestants and Catholics, Loyalists and Irish Roman Catholics together at Belfast City Hall. I think we’ll be hearing from some innocent victims of violence from both sides at this conference. But so far, clergy haven’t been targets for the gunmen”.

In our two-decker bus, every seat is taken, and the aisles are full of luggage. Along the way, I play the shakuhachi quietly, to accompany the day-dreamy music of Irish singer Enya as it streams languidly from the speaker in the luggage rack above us.

Colum leans over and points outside, “Sounds nice,” he says. Meeting Enya’s meditative voice with some long shakuhachi tones brings a wonderful, healing counterpoint to the images of hatred and violence that Colum has portrayed.

Thankfully, the bus ride into Belfast and the cab ride to our Holiday Inn are uneventful. I am nervous about the possibility of random violence. Colum and I get our rooms at a Holiday Inn and then take a cab to the Waterfront Hall, a vast new convention center with two large auditoriums. All around the Hall, new construction is going up in every direction. A sharp contrast, the taxi driver tells me, with West Belfast which is still poor, and the continuing focus of eighty years of violence. As we slow to a stop in front of the Hall, the driver points to a tall crane a few blocks away. “That’s where the Titanic was built,” he says.

Before coming to Belfast I had talked by phone with the conference coordinator, Simon Keyes. “I’m delighted that you can play your flute,” he said. “If you can arrive in Belfast on Wednesday, please come to the rehearsal for musicians on Wednesday evening. I have passed along your name to our music coordinators, Cecelia and Chloe Goodchild who will let you know more.” Well, this is Thursday morning. Since I wasn’t able to get an earlier ticket, I missed the musicians’ gathering. Still, I hope that Cecelia and Chloe have made a place for me. At the Way of Peace gatherings in India and Italy we were a smaller group, so we didn’t need a music coordinator. In India, Fr. Laurence simply gave me or John Drury, the folk singer, a sign when he wanted us to play. And in Italy, I was the only musician. But Belfast would be different. I’ve heard that there will be about a dozen musicians here. But right now, I don’t even know if I’m playing.

It is 10:30 in the morning at the Waterfront Hall. I recognize Cecelia from her picture on the Conference website page. She’s standing with a man and a woman, each of whom carries an instrument case.

“Hello Jonas. How good to see you. We weren’t sure whether you’d be here, but we have penciled you in for a couple of solos and some duets. We hope this is O.K. You’ll play a solo today, right after lunch, a lead-in for one of the afternoon meditations. Later, you’ll be part of a duet, if you like.”

The World Community for Christian Meditation (WCCM), sponsor of this Way of Peace dialogue with the Dalai Lama, closed registration many months ago when the maximum number for the auditorium, 400 people, was reached. Hundreds more are on the waiting list. Most of the participants are Christians who meditate and who see a kindred spirit in Tibetan Buddhism. Of the one-hundred or so Buddhists who are here, most are Tibetan Buddhist. I see on the list of teachers three friends of mine: Norman Fisher, a Zen master from San Francisco, Robert Kennedy, a Jesuit Zen teacher from new Jersey, and Fr. Kevin Hunt, a Trappist monk from Massachusetts who is also trained in the Zen tradition.

The Way of Peace literature points out similarities between the inter-sectarian violence here and in other parts of the world such as Tibet. So, perhaps it’s not surprising that this visit by the Dalai Lama, a Nobel Peace Prize recipient, has been receiving good press in Ireland. Many people are curious. What lessons about non-violence from the Buddhist tradition are also relevant to this conflict? Of course, there are other voices in the papers as well. Some letters to the editor express a view that the Dalai Lama doesn’t know the local situation and shouldn’t come here “telling us what to do.” My opinion doesn’t matter much. I’m a stranger in this land. But my hope is that the Dalai Lama’s wisdom, and Fr. Laurence’s Christian wisdom, touch on universal truths. In India and in Italy, I have heard His Holiness say “My religion is happiness, the true happiness of each person.” I am sure that Jesus and every Christian, whether Protestant or Catholic, would agree. Why is it so difficult for people of different faiths to focus on this universal human goal of happiness? I’m here to investigate.

At 1:30 in the afternoon I stand in the darkened wings of the auditorium. As I look out, I see rows of theater chairs on either side ascending toward the three-story high ceiling. Talks by His Holiness and Fr. Laurence and by various spiritual and political leaders will take place here on the auditorium floor. The musicians will also play here, standing on the Irish earth. Out in front of me, in the middle of the floor, is a ten by thirty-foot box of Belfast dirt, and in the middle of that three chairs and some microphones stand on a square of carpet. After some introductory remarks, I will walk out to the dirt to play a solo piece. In the shadows, I lean down to take off my shoes and socks. I want to get closer to the Irish earthen spirit as I play.

The seats are almost filled now, and the din of hundreds of conversations is dying down. At a signal from Giovani Felicioni, the producer, the house lights go down. Giovani squeezes my arm, smiles and nods. Time to go. I feel the warm brightness of a spotlight making the air glow around me as I stand on the cool earth of this beautiful and conflicted land to play Kyo Rei (empty bell).

Luckily, I remember to take a very big breath before the first note. This first breath is important. It grounds me within myself. Hundreds are watching but I am alone.

Since I will not explain the shakuhachi and its Zen sensibility first, I want this first note to be a long one, long enough for everyone to realize that there will be no melody. I trust that this crowd, in particular, will understand Kyo Rei right away. Almost everyone meditates. They know about silence, and perhaps they see the analogy, that chasing after melodies can be an escape from the inharmonious but creative chaos we face when we close our eyes, do nothing, and listen to one breath at a time.

As I breathe into the following phrases, I see my mind at work, creating sentences, reaching out for meaning. And I see it letting go of these same creations. Is this what a contemplative practice could offer to communities in conflict, the ability to see the roots of violence in our minds and hearts? I make a mental note to bring up this link when I lead my workshop later.

I have been reading modern Irish fiction–and the historical record–about the last thirty years of violence here in Belfast. Even as I blow, one note at a time, I see the flash of gunfire and follow it back to the mind behind the trigger. Somewhere in those shadows, the image of another person emerges. Thoughts coalesce around the image, thoughts like “that son-of-a bitchen traitor!” “He will pay for this, the treacherous bastard!” The images and thoughts take on a solidity and an electric, heavy presence in the limbs. This dark, archetypal figure is putting together a bomb, to plant it “where that mother-fucker will get what he deserves; to shoot into his animal mind at point-blank range”. I sense within me this hard purpose of the universal reptilian mind, that if I murder this person, I will stop the suffering that bleeds into every corner of my life. Life will be better when this bastard dies. Across the span of several breaths and simple notes, I am watching the germinating seeds of war in my own darkened heart.

But–ah, the sheer grace–I see the thoughts as separate from me. I am not my thoughts. Thoughts and images come and go as I blow each long note. I am not acting on them, not jumping in with my body to enflesh the thoughts. They are only thoughts, but they make me stiff.

What if we lived in communities where thoughts were so visible and transparent? What if we all grew up with this kind of inward mindful discipline? Maybe this is one reason I have brought the shakuhachi here, to offer this opportunity to myself and to others. Will this music, this note-at-a-time, this silence between each note, help others see how violence begins in one’s own mind and heart?

I know this goal is grandiose. So few people are inclined to take up the discipline of meditation. So few are excited by this practice of loving, moment-to-moment detachment from thoughts that both Buddhists and Christians hold up as a central goal of the spiritual life. Still, I’ve got to play anyway. How can I respect myself if I don’t allow for a slim chance? Maybe this is the same slim chance that motivates Fr. Laurence and His Holiness to come to Northern Ireland. What else can they offer? They don’t know the facts, the complexities of the political situation. But they do know something about the human person. Kyo Rei is a small gesture in their direction.

As I blow into the silence I sometimes glance up to see that almost everyone’s eyes are closed. I am blowing from the heart, hoping that they are listening from the heart. Is it grandiosity or pure prayer when I trust that Kyo Rei’s invitation to loving detachment will ripple out to everyone here in Belfast?

Sure, I’m an outsider, but I don’t feel like one. Occasionally, I glimpse potentially hurtful anger in my belly. Driving through Boston traffic can bring it out. Seeing my political leaders make decisions that hurt our planet’s fragile ecology can bring it out. Anger can be an appropriate response to injustice. But it’s a tricky thing. Undisciplined, untransformed anger might only make matters worse. How to harness the powerful energies that are released when we see unnecessary hurt and suffering? I don’t know how to do it, but I want my shakuhachi and me to be part of the solution.

Later in the afternoon I play Daiwa Gaku (Great Peace) and Kojo no Tsuki (Moon over the Ruined Castle) as the hundreds of participants enter into and out of several twenty-minute meditations. I am happy to make this contribution to a gathering that includes so many people who are out on the streets of Belfast and in other communities, working for inter-religious peace.

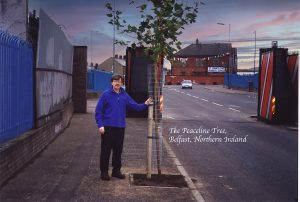

Jonas at the Peaceline tree, Belfast Northern Ireland

At every transition between speakers and meditations in this Waterfront Conference Hall there is music from different combinations of the twelve musicians who have come. In the midst of the silence and the music Fr. Laurence and the Dalai Lama come and go from the hall. They travel around Belfast together, planting trees at the “Peaceline”, the high wall that separates the Protestant and Catholic communities, and meeting with local politicians and people traumatized by the violence that has taken 3,000 civilian lives in the last thirty years. Throughout this week, our leaders will meet with local Buddhists and Benedictines to pray for peace.

Today, at the Belfast City Hall, Fr. Laurence and His Holiness convene a one-day Youth Conference on the theme, “Non-Violence Works”. And, this afternoon, 250 young people will see this Roman Catholic monk and this Tibetan Buddhist embrace and then lead them in meditation and a lively discussion of non-violence. The sheer improbability of these Christian and Buddhist leaders leading us in silence has got to make a difference.

One of the afternoon speakers is the First Minister of the Loyalist party here in the North, David Trimble. Like the Dalai Lama, he is a Nobel Prize Winner. When he steps out onto the dirt in his business suit and polished black shoes, Trimble sports a white scarf of blessing around his neck, given to him by the Dalai Lama. He tells us, “people here are ready to settle old differences because we see our common humanity.” Turning to the Dalai Lama, seated beside him, he smiles and says, “Your visit will be remembered as offering a positive contribution to the way of peace.”

I am sitting next to an old woman from West Belfast who has been telling me about the terror of “the Troubles.” After I had played Kyo Rei and sat down, she whispered to me, “I moved here from the south twenty years ago. My brother was wounded in the Troubles, but you have to trust that the Holy Spirit will help. Well, sometimes, you don’t trust, but you try to help anyway.” She closes her eyes and shakes her head slowly from side to side.

When Seamus Mallon, the Deputy First Minister of Northern Ireland comes forward and looks up into the spotlights I know what he sees—partly blinded by the intense light, all these meditators are a ghostly presence, like a crowd of witnesses hovering over the ground. What is he thinking? Does he sense the intensity of hope in this room? When it comes to the hard questions of war and peace, can these politicians be influenced by spiritual forces? I know I won’t have an opportunity to ask these leaders directly. They are whisked in and out by their security people. Seamus says only “I am proud and honored that you, your Holiness, are here. Your symbolic walk through the Peaceline today points us to the way of friendship. We have seen violence. You have seen violence. We must not forget those who have died and suffered, and yet we must leave the past behind, to make a fresh start. You have helped us to do this. When you, your Holiness, leave these shores, you leave as a friend”.

Bobby Sands, a Catholic in the Protestant community, an IRA fighter, dies in prison

Finally, Peter Mandelson, the controversial British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland stands to say, “We are here because so many leaders have taken risks with their parties, constituents, and communities. They have paid a big price for their leadership. You only have to think about how life in Northern Ireland has been transformed, and how much is at stake if we slip backward.” Everyone in the room knows what he means. In past weeks, newspaper headlines feature renewed violence between Palestinians and Israelis.

“How very near the surface are deadly passions waiting to be unleashed. We must not make a wrong turn.”

Then Mandelson pauses and turns to the Dalai Lama, “It has been so powerful to see your presence here, and then to see the unionist leader and the nationalist leader here, to share this vision of peace”. A chill runs up my neck and tears suddenly well up in my eyes as I hear these words of hope. The old woman next to me is crying too. With Mandelson’s last words she touches my arm and says softly, “In Jerusalem too”.

Now, the lights in the auditorium come down as two spotlights suddenly illuminate a tall blond woman and a wild-looking man walking out onto the dirt. She is the Irish singer Dierdre Chinneide, and he is an Englishman, Michael Ormiston. Their duet will introduce twenty minutes of silence. Michael carries an old wooden 2-stringed lute from Mongolia. His long, unruly blond-red hair flies out from underneath a blue and gold cap that looks like a beehive. Michael sits on a chair next to Dierdre, holding the lute in his lap.

After a moment of silence, Michael draws the bow slowly across the horse-hair strings. A wavering, eerie tone fills the air. Dierdre, standing with eyes closed, opens her mouth slightly and makes an oscillating, droning sound with her voice that harmonizes with Michael’s strings. And now she leaves the drone and opens into a lovely song in a familiar Irish key. Michael’s lute moves alongside, in the background, lending three dimensional depth to Dierdre’s gorgeous melody. With closed eyes, she sings in Gaelic. I don’t know the words, but I sense this is about love, a big, transcendent love.

By imperceptible degrees, Dierdre’s voice is increasing in intensity and volume. Her face is radiant in the spotlight and her hands are raising up from her sides as she sings. Soon, she is lost in the beauty of the song, her open hands and outstretched fingers reaching upward. I feel that I am seeing a love song disappear into God. As her voice trails off, another sound emerges from the darkness. It is a gutteral bleating, somewhat like the overtone singing of Tibetan monks, but with the addition of something like a whistle sound. It is coming from Michaels’ throat. This is the uncanny Mongolian throat chanting that I’ve heard about. I am mesmerized.

The combination of Dierdre’s rich, romantic voice and Michael’s overtone Mongolian chanting is unearthly. And yet it rushes into me like the voice of the earth itself, as if the earth itself is crying out in polyphonic overtones of love and suffering. After Dierdre’s last note goes up into the light and darkness, there is a five second silence. Then Michael leans forward into the microphone to release one long, steady, toneless outbreath. I am stunned. It seems that I have never heard such beauty.

In the next twenty minutes of silent meditation, as I continue to hear the inward echo of Michael’s strings and chant and Dierdre’s voice, I feel a new freedom for me and the shakuhachi.

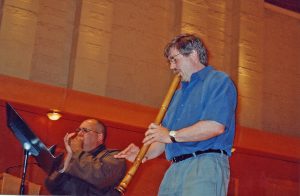

I’ve had just one public collaborative experience like theirs. This past August I was playing shakuhachi at the Society for Buddhist-Christian Studies conference at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington. I had already done a couple of solos in PLU’s beautiful new concert hall when I met a Buddhist monk, Rev. Kusala, from Los Angeles. He mentioned that he played the blues harmonica and used it in his prison work with teenagers. After improvising together for a half-hour, we decided that at the evening’s concert, he’d join me at the end of an old Sui-Zen piece called Matsu Kazé (Wind in the Pines).

So, that night while I played, he sat beside me on the stage in his Zen robes. Then, as I blew the last note of Matsu Kazé, Kusala got up, brought the harmonica out of his pocket and began blowing steadily in the same pitch. Soon, we were picking up steam together for a few miles, and then I dropped into the background and played a simple drone accompaniment to his stunning southern blues piece. We got a standing ovation from the delegates. It was my first public improvisation, and I was thrilled. I felt guilty the next night because as I rose to play, I saw a Japanese delegate walk out of the hall. I imagined that he was upset that I was mixing traditional Japanese Zen music with blues. My shakuhachi tutor, Yodo Kurahashi, had told me that he knew many shakuhachi masters who could not tolerate western music. Who knows why he walked out? But I was alerted to a conflict within me, and a new realization that perhaps it is time for me to step out of the pure Sui-Zen music into something that is more. . .well, more me. Playing with Rev. Kusala felt liberating and seemed to bring joy to others.

So, that night while I played, he sat beside me on the stage in his Zen robes. Then, as I blew the last note of Matsu Kazé, Kusala got up, brought the harmonica out of his pocket and began blowing steadily in the same pitch. Soon, we were picking up steam together for a few miles, and then I dropped into the background and played a simple drone accompaniment to his stunning southern blues piece. We got a standing ovation from the delegates. It was my first public improvisation, and I was thrilled. I felt guilty the next night because as I rose to play, I saw a Japanese delegate walk out of the hall. I imagined that he was upset that I was mixing traditional Japanese Zen music with blues. My shakuhachi tutor, Yodo Kurahashi, had told me that he knew many shakuhachi masters who could not tolerate western music. Who knows why he walked out? But I was alerted to a conflict within me, and a new realization that perhaps it is time for me to step out of the pure Sui-Zen music into something that is more. . .well, more me. Playing with Rev. Kusala felt liberating and seemed to bring joy to others.

Now, in the Belfast Waterfront Hall, Michael and Dierdre have unknowingly given me permission to bring even more of myself into my music. Their offering allows more emotional depth and more heart-felt passion than I’ve experienced through my Japanese Sui-Zen pieces. And I want that for myself.

A bell rings as everyone stands. The Dalai Lama re-enters the room. He, his translator, Geshe Thupten Jinpa, and Fr. Laurence walk to their chairs on the carpet.

Fr. Laurence says to His Holiness, “It’s been 2 or 3 years since we met in Dharamsala and spoke about a pilgrimage to each other’s sacred sites. In Bodh Baya we met under the Bodhi tree and discussed salvation and enlightenment. Then we welcome silence and dialogue together at our monastery in Italy. And finally we decided to bring our dialogue to a place of conflict, to show, as a small sign that the spiritual life is not just for churches and monasteries.

“When we thought of such places and mentioned Belfast, your eyes lit up and you said yes. And so, here we are. When we think of religious harmony, we wonder how it can contribute to peace in Northern Ireland. In Christian scripture we read of a ‘peace that passes understanding’. Your Holiness, what does peace mean?”

The Dalai Lama leans onto one side of his chair to speak into the microphone. “I think that for both the individual and society, peace is the fact of leading a meaningful and happy life. Of course, one must start with the individual. The individual is the key factor. Each person must come to a happy, calm, sound view of life.”

“And,” he adds with a smile, “this happiness must also include birds, insects–and even vampires. Of course, even those dangerous mosquitos have a place!” Knowing that Buddhist ethics forbids killing of any living thing, everyone laughs. His Holiness shakes his head and chuckles, “I think the mosquitos are exceptional.”

Fr. Laurence is a gifted spiritual teacher in his own right. But, perhaps because he recognizes the power of the Dalai Lama’s fresh presentation of ancient truths, he often invites his friend to speak first, and at greater length. Fr. Laurence wants to know how spiritual practices can help when communities come into conflict.

“Every day I meditate on love and compassion,” smiles the Dalai Lama. “No problem to meditate on these things. But of course, it’s even more difficult than that–after the meditation, then you must live with your neighbor!”

With jokes like these, His Holiness implicitly acknowledges a long-standing Christian criticism of Buddhists, that they are “world-denying” or nihilistic in their emphasis on private meditation and personal enlightenment. Many non-Buddhists find it hard to believe that all the world’s problems can be resolved on a meditation cushion.

But then His Holiness turns us back to the cushion when he adds, “Sometimes there is a degree of unreality in meditation on compassion. Because, we have a beautiful meditation, but then in the real world we go out and exclude certain people from the category of compassion. We must make a special effort to concretize the object of meditation to include meditations for enemies.”

Fr. Laurence reminds us of Jesus’s heartfelt vision, that it is easy to love our friends. But the real challenge is to love our enemies. So, both the Dalai Lama and Fr. Laurence see the roots of social conflict in the heart of the individual. Each sees the category “enemy” as a sinful or illusory construction of the individual mind and heart.

“When we look inside,” says the Dalai Lama, we find that ‘I’ is there.” He sweeps his hand across the space in front of him and adds, “‘I’ can be the creator of a whole universe, and sometimes it’s not the real universe.”

When the laughter dies down, he says, “This ‘I’ makes differences between ourselves and others that aren’t really there. This ‘I’ can bring a conception of I-They, inside and outside.” Speaking of how this ‘I’ shows up in his part of the world, he smiles again. “Sometimes, this ‘I’ thinks, ‘India is the center of the world!’”

Laughing with His Holiness, Fr. Laurence adds, “Or that Jerusalem or Rome is the center!”

“Yes.” The Dalai Lama smiles, “Most of us think we are at the center of the universe. In a way it’s true. But if we don’t reflect on our deeper identity, we focus on a very limited area of personal concern and lose a long-term view. We don’t see how our own interests are linked with others, especially in these modern times. Now, my future depends on others’ interests. So we must promote a sense of caring and respect. Then non-violence follows. Always, we must meditate on the consequences for others as we work for ourselves.”

“I agree with you,” Fr. Laurence responds. “Each side must put self in the mind and shoes of the other. But this requires an effort to put your center in them for awhile. Is that what you mean by caring for others?”

“Yes. I believe in non-violence because it is an expression of compassion. We have to treat other nations as our own. At both the personal and the national level, hurting others is hurting ourselves.”

Fr. Laurence nods, “This connects with an understanding of Christian sense of God. Many Buddhists—and some Christians–think that God is a higher being, an Other. But that is only one-half the story. The other half is that all beings are interconnected in God. God is the center that is everywhere. Therefore the deepest center of ‘me’ is also the deepest center of you.” His Holiness nods quietly, and I think of Jesus who, when he knows that he will soon die physically and yet, in a sense live forever, tells his friends not to worry. He says that he lives in “the Father,” the Creator, who is eternal and that “I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you” (John 14:20). We too, are living both mortal lives and eternal lives.

The room is dark, except for the floodlights on these three men sitting on chairs, on a small square of native earth. The light has been adjusted toward orange tones, something like a sunset. After a pause in the conversation about interconnectedness, His Holiness invites more laughter when he says, “Perhaps it is easier for me. I have no country, so unless I claim citizenship of the world, I have no citizenship. I belong everywhere and to everyone. And this is true for all of us.”

As I look around the room I wonder what others are making of all this. Many of us have found some peace, and a larger perspective through meditation, Christian or Buddhist. Some of us probably believe that our particular way of meditating is the best. It’s only natural to want others to find the joy or truth that we’ve found in our own tradition. But many of us know the danger of thinking that “we” are right and “they” are wrong.

I have some friends who are anti-religious. They think that religion is the source of evil because it always promotes a hostile division between people, between “us” and “them.” In the intellectual atmosphere of my home near Harvard, blaming religion for world conflicts is a common sport. This conflict in Northern Ireland proves my friends’ theory. Neighbors can be alike in every respect, but because one goes to a Protestant Church and one to a Roman Catholic one, they must hate one another. So I am interested when these religious leaders say that their spiritual practice provides a special place for those who are different. I’m reminded of the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas who explore the value of our awareness of otherness. What is that value, but to bring an opportunity for us to discover something about the other and about ourselves.

His Holiness adds, “Many of the six billion human beings on this planet have no interest in practicing the moment-to-moment disciplines of religion [In 2023 this number is now 8 billion]. But we have to take care of them also. Such millions of people have a right to be happy, just like me. And you know, we will never convert everyone to our way. Many people will not ever accept Buddhist teaching.” He pauses, smiles, and then adds, “I shouldn’t say this, but Buddha is a failure.” And I am thinking, well, Jesus was a total failure-murdered at age 33, while Buddha lived into his 80’s.

“I think many Christians have had this same delusion,” Fr. Laurence says. “Fundamentalism of any sort quickly gets out of touch with reality. There are many identified Christians in the world. About one-third of the world’s people say they are Christian. But we cannot know how many take the practices of love seriously. In fact, the world will never become Christian, and all Christians won’t meditate or pray daily. This is a difficult thing to accept for many Christians. But in the name of Jesus, we cannot make ourselves right and others wrong. This leads to violence.”

“Of course,” Fr. Laurence adds with a smile, “we could settle for merely being polite with one another.”

His Holiness bursts out in laughter and touches Fr. Laurence’s arm as Fr. Laurence continues, “But to work with reality, to work with conflict, this is the point of a contemplative spiritual life. This is how we pass through the death of the ego “I”, emptiness and the cross. We seek to go deeper than our opinions about others. We seek Christ’s self-emptying love. So, the contemplative tradition is most important at this time in history.

“Today the world is more interconnected. Religious identity is part of the global family. Today we must have a sense of rightness and goodness for both self and other. This does not mean that we make all traditions the same. I think it is possible to remain deeply rooted in one’s own tradition while also cultivating contemplative detachment. We must reach for this larger religious identity.”

I feel inspired to hear these words of reality and hope from His Holiness and Fr. Laurence. The hope they offer isn’t an easy way out. Their hope is founded on the principle that each person must take responsibility for his or her mind, and for the seeds of love and hate that are there. Concurrently, we must act, to help others find a way to individual and community peace. So far, Japanese Sui-Zen has not communicated these important connections and values explicitly to me. But the connections can be made, and this Belfast experience is helping me to see them. Blowing Zen is a meditation, but it is more than proper form, good technique and relaxation. Within each breath is the nesting ground for myriad possibilities of connection and healing with others.

The next morning, after a fitful sleep, I take a taxi from my hotel to the Waterfront. I am tired. From two until four in the morning, a drunken man was standing against a door in the hallway a few doors from mine, drinking beer. Every fifteen minutes or so he’d kick the door several times with the heel of his shoe. I heard the voice of a woman behind that door. It seemed that absolutely didn’t want to let this guy in. I wondered if he had a gun. All the violent images I had in my head about Belfast came to mind. I gingerly looked out the door twice, wanting and not wanting to be seen. No result came from my repeated calls to the front desk. Rummaging around in my baggage, I finally came upon some old earplugs, stuffed them in and hoped that no one would get hurt. When I walked out into the hall at seven o’clock in the morning, there was no body, no blood, no beer bottle, no sign of the man. I dismissed the idea that this incident was directly connected to The Troubles, but still, I left the hotel with the uneasy feeling that an outbreak of violence could be imminent.

At the Waterfront Hall, I am happy to find the music coordinator, Chloe, standing near the table where the musicians hang out. I ask her if I’ll be playing shakuhachi again.

“Oh yes, of course,” she says, as she gets out the schedule. “Here you are. Today you’re paired up with the English soprano saxophonist, Ed Jones. You and he are scheduled to play at 2:30 pm, just before a meditation. Why don’t you meet him here about 1 pm?” Great!

At 12:30 I am at the table, talking with some Irish musicians. The Irish singer and harpist, Annie Mawson is tuning her wooden Celtic harp. We start talking music, and soon we are playing with chords and notes, weaving some shakuhachi into a sacred old Irish song. I am thrilled to play with a harp for the first time.

“Very nice,” says Annie. “Let’s look for a chance to play.”

At one o’clock I see a man leaning over the music table, looking at some of the CD’s for sale. He is carrying an instrument case. Must be Ed Jones. I say hello. Ed has a sharply jutting chin, bags under his eyes, jet-black hair slicked backward over his scalp, dark eyes and a ready smile. I ask if we can play something together. Sure, he says. Because we don’t have much time, we agree to look for a room to practice.

We go to the Green Room where I will lead the “Music, Meditation and Metanoia” workshop later in the afternoon. We close the door, take out our instruments and share stories about them. He is interested in the history of the shakuhachi and charmed by the Japanese music notation.

He tells me about his soprano saxophone. Most soprano sax’s are straight, but this one is curved. “How remarkable that we both have a Japanese connection”, he says. “I first saw this sax at a display by a Japanese saxophone maker. I started fooling around with it, and it sounded really distinctive. I was taken with it right away. But the salesman didn’t believe in it. It’s curved and rare, and I don’t think he appreciated what he had. He tried to talk me into buying a more popular style. So I surprised him when I was so insistent. Finally he agreed to sell it to me at a reduced price. It was perfect.”

Could these two, very different instruments work together? Neither of us had ever heard a soprano sax/shakuhachi duet. Now, we have less than an hour to get something together. We begin blowing through our instruments, experimenting with different clusters of notes. I move in and out of some honkyoku pieces.

“Why don’t you take the lead?” Ed suggests. “I can follow you and figure out the key.”

Japanese shakuhachi notation for Kyo Rei (Empty Bell)

This is new for me, to think in Western keys with the shakuhachi. I have brought along a little chart that shows the notes in each key. After finding a bunch of pitches that work, I consult the chart and figure out that I’m working mostly in the key of G. I can skip by the occasional non-G notes.

“O.K.” Ed says, lifting the saxophone to his lips. “G is good. Try it again.”

This is fun. I’ll put together a nice progression by cutting and pasting from several different honkyoku, and hope that I don’t offend the Japanese people in the audience. Ed listens with his instrument, moving in and out of my progressions with the most extraordinary agility. Soon, I forget he is playing with me, except when we hit some notes that seem too dissonant. We’re dancing.

I’m nervous, not feeling professional as a musician (because, in fact, I’m not). But some uneasy dissonance is O.K., a wake-up call that makes the beauty real. But even a little too much dissonance is painful to the ears and makes the players and listeners self-conscious. In my heart, I want to play something beautiful, but I’m restrained by the reality that I’m still a beginner. Still, I have a perhaps naïve belief that a player’s sincere desire for beauty will call forth and receive support from Beauty itself–that Beauty that is in God and wants to be expressed.

Technical proficiency is vitally important, real beauty transcends our ordinary rules of beauty. Japanese Wabi sensibility sees how imperfection and ugliness can be beautiful. And Christian eyes can see Easter circulating within humiliation and defeat. I sense that Ed knows these things. When we play something that doesn’t sound right, I can hear him adjust himself around it, to make the “not right” fit. I think this must be how wisdom shows up in music.

At one point during our little practice session Ed and I are cooking, and a chill of pleasure and joy sweeps across the hairs on my back and arms. I start laughing and have to stop.

When I look up, Ed is smiling too. “I think we’ve got something here,” he says.

“Yep, very nice. Let’s go.”

At 2:20, Ed and I are standing in the wings of the auditorium floor, on opposite sides of the big box of dirt. We are watching Giovani for a sign. Now, the house lights come down as the spotlights illuminate the places at our microphones. Ed and I know the cue. We have taken off our shoes, and walk out onto the dirt in bare feet. We have agreed that I’ll begin with the first few notes of Daiwa Gaku, Great Peace. He’ll come in on the third phrase, on the same note. We haven’t agreed on a definite melody or rhythm. I’ll step off the edge of Daiwa Gaku. It will be free form, hovering in the vicinity of G.

A few minutes before going out I suggested to Ed that the duet be in the shape of a mountain. We’ll begin with simple notes in a low octave. Then, we’ll gradually increase the pace and power, reaching an intensity of beautiful but precarious chaos at the top. Gradually, we’ll descend the mountain toward a place of peace that includes what we’ve seen at the summit. I’m thinking that real peace isn’t separate from the aggressive energies that can turn to violence. It isn’t separate from fear and desire. It’s got to include and transcend what we like and don’t like about ourselves. Ed laughs, “I’ve heard of mystical theologians, but you’re a musical theologian! Sure, let’s go with it.” So, here we are, spotlighted in front of 400 people, trusting that we’ll know how to do it when we get there.

We find our places, and both stand still and silent in the spotlights for a few seconds. Slowly, we raise our instruments to our lips. Then, keenly aware of each other’s presence across the dirt, we close our eyes and play. I hear Ed’s echo from the speakers in the great hall, streaming across the dirt and lights, and he hears mine. We play off each other, and I hear sounds I didn’t know that a saxophone could make. In turn, I blow phrases that I’ve never played before. Here and there, it’s American blues woven into a Japanese Zen tapestry. An image of Rev. Kusala in Tacoma zips through my mind. I wish he were here with his blues harmonica. I am hearing breathy, bamboo-like sounds come from the saxophone, and I feel a twinge of jealously, wishing I could play a saxophone like that. But then I am back into it, enjoying the freedom of those techniques that I’ve mastered.

When I blow hard and steady I am Jesus turning over the money changers who desecrate the holy temple; I am pushing last night’s drunk man up against the wall, kicking his beer bottles down the hall and ordering him to leave this woman alone and go home; I’m ordering the Chinese out of Tibet, fighting fascism, calling Lazarus out of the tomb.

And then I am back in the sky. Flying. At the top of the mountain Ed and I circle each other, like birds ascending and descending in spirals past one another. He goes up the scale while I go down. And then suddenly we are both ascending like young brother birds into the sky.

Now we are chasing each other, and it’s not playful. One is a hungry hawk, moving quickly in a low register, trying to catch swift high-octave bird. But now predator and prey forget themselves in the sheer pleasure of flying, sprung for joy.

At the very top, we are both in the upper octave with pure notes commingling freely with eruptions of messy overtones, driven by one wind in many dimensions. We are a clouds of birds are rushing through each other in whirling spiral that ascends through the clouds and beyond. Then, gradually, we descend, losing and finding each other over and over. We are remaining in the low octave now, and slowing down.

Glancing up at each other, we each bow slightly, the pre-arranged sign we’d give to indicate two more long breaths to end. We breathe in together and blow the second-last long note. They are different notes, but they work beautifully together. I throw in a pulsing breath from the diaphragm to suggest some new life stirring in the end. Ed mirrors me with his own pulse. These notes that work so well must be different by a fifth or a seventh, I don’t know enough music theory to know. The thought that I should study western music formally crosses my mind. But the thought, all thought, disappears as we both blow the last note. It’s the same note, extending and trailing off. We disappear together and then stand still, letting the echo of the mountain journey circulate in our bodies and in the room. Finally, we bow and walk off as everyone dwells in the quiet of the twenty minute meditation.

When the meditation ends, Ed comes around to the hallway where I’ve been sitting. We smile broadly and hug. “That was fantastic, brother,” he whispers.

“Absolutely,” I say as I point upward through the ceiling to the sky. “That was so much fun. Thank you.” I add, “You echoed the shakuhachi so beautifully. I didn’t know a saxophone could do that. Maybe because these Japanese sax makers have the shakuhachi sound in their bloodstreams.”

“Right. Beautiful,” Ed says. “I’ve got to go to a rehearsal for a gig tonight. Let’s play again.”

Later, as I walk through the halls a dozen people thank me for the duet with Ed. One man, from London, says, “It was so incredible, one of you on each side, and then calling and responding to each other, from East to West. I’ll bet this is a first, the soprano sax and the shakuhachi meet!” He is thrilled and I am still in heaven, still dancing with Ed and the eagles.

After the saxophone and shakuhachi duet I head up to the Green Room, a hotel conference room without windows, to offer the “Music, Meditation and Metanoia” workshop. I had understood that we’d have about twenty people, but when I walk in the room there are over forty people waiting to hear what I have to say. Me too. Though I’ve thought a lot about what I’d say, I haven’t written anything down. I’ll trust in the Spirit.

The one-hour workshop flies by. I play a simple honkyoku, Cho Shi, at the beginning, and then use its translated title, “Tuning Heaven and Earth”, as a way to talk about playing the shakuhachi. I give a half-hour talk about how I connect Sui-Zen with Christian prayer and then take questions. Many hands pop up continuously for the rest of the hour. Even though there are several Japanese people in the room, no one has seen the Japanese musical notation for Sui-Zen. I pass around several honkyoku scores as we talk.

A middle-aged Anglican priest from London asks, “This is so interesting. You’ve spoken about metanoia, about the change of heart and mind, that can come with shakuhachi’s meditation music. Makes sense. But traditionally, metanoia is what happens when you turn to Christ. There is no necessary connection between Blowing Zen and God, is there?”

“Good question. No, there isn’t. Each shakuhachi player brings himself, or herself, to each breath. I suppose that a Muslim player might experience his breath as a gift of Allah, with all the connotations that go with that.

“You see, Zen and Blowing Zen integrate easily into any religion because they don’t offer a rival set of beliefs. Buddha didn’t take a position on whether God exists or not. That wasn’t his question. He was concerned with training our minds to let go of all distractions and to be fully present in this moment. If God is present now, then Zen can help. If God desires our transformation in each moment, we’ve got to be present to receive it. So, for me, Blowing Zen offers an opportunity to wake up with each breath.”

I find the rest of the discussions in the Green Room exciting and inspiring. Having to respond to people’s fresh and sincere questions challenges me to find words for what is essentially a wordless activity, making music. Putting words on music, meditation and metanoia helps me to get my bearings in a sea of mystery.

The next morning I am standing in a doorway off one of the great, high marble corridors of Belfast City Hall. I peer into a big auditorium where seven hundred chairs are set out for today’s program. Soon, we will hear from Mary Macleese, the President of the Republic of Ireland, Fr. Laurence, the Dalai Lama, and several victims of sectarian violence in Northern Ireland.

As I look out, Heather Innes, a Scottish singer with a round, sad face, approaches me with a shy smile. Heather and I shared stories about our music on the first day of the conference and when Chloe suggested yesterday that Heather and I might do a duet today, we spent a few minutes on some old Scottish tunes, looking for shakuhachi connections.

Now, Heather says, “I have an idea for today. Remember that sung-prayer, ‘Escomb Prayer’ that we looked at yesterday? Could you accompany me as I sing it this morning?”

“Sure.” I say. “Let’s find a place to practice.”

I have brought two Japanese bamboo flutes with me to Ireland, the standard 1.8 shakuhachi, and the longer 2.4. For the entire week I carry the flutes in my blue backpack. Behind me, they stick out of the top of the bag, with the 2.4 flute rising up to the top of my head. I’m proud to be a musician, though I’m still not used to the word, musician. It seems too formal, suggesting that I’ll be held to some professional standard. I’m more comfortable with the image of being a wandering good-guy shaman like the Chinese martial arts expert Kwai Chang Caine in the 1970’s television series, Kung Fu. His music came spontaneously from the heart, always in response to a unique, present event, and always contributing to his goal of helping others.

Sometimes I am self-conscious about how these flutes-in-the-bag look, especially in times and places of conflict. Once, during an international security alert related to a Middle East conflict, a security guard at Logan Airport wouldn’t let me take my shakuhachis on board the plane. “How do I know they’re not weapons,” he wanted to know. So, I took a flute and some music out and played him a few lines of Matsu Kazé right there by the x-ray machines. Then he let me go. And then in India, the first time that the Dalai Lama’s guards frisked me, they wanted to look closely at every flute. Now, I’m wondering if the many guards up and down these City Hall corridors think that these sticks are weapons. As I walk down the hall with Heather, I try to appear like a clean-shaven, naïve, American tourist. Which I am. Hey guys, I’m on your side.

When I walked into the City Hall grounds this morning, small groups of RUC (Royal Ulster Constabulary) police stood at every entrance. The RUC is the legal police force of Northern Ireland, charged with protecting all residents, regardless of religion. But it turns out that the RUC is composed primarily of Protestants who are loyal to Britain, and it is hated by many local Catholics who feel oppressed by Britain and its police force. Under the new peace agreement, the RUC is supposed to include more Catholics. But everyone wonders if the deeply rooted hatreds between Protestants and Catholics can ever be healed. Now, the RUC “bluecoats” are standing about every ten feet in these labyrinthine corridors, looking closely at the men and women beginning to wind their way up the staircases.

My Irish friend, Colum, has told me about this building. As I look around I see cavernous hallways lined with large paintings of British nobility, all white males. To many Catholics, Belfast City Hall is the power center of British imperialism, the home-nest of the Protestant queen bee. I assume that it has been a prime target by the Irish Republican Army (the IRA). As people stream into the great hall, I approach a man in a business suit. He is a plain-clothes cop, talking to the uniformed RUC policeman beside him. The two of them have been directing people away from the hallway behind them. At the end of the hallway is a tall, glassed set of double doors, with more doors behind them.

“Excuse me sir.” I say, “We are two musicians, looking for a place to practice for our performance. I wonder if there is an empty room behind those doors?” The man has coiled black wires coming out from under the back of his shirt collar, ending in a small listening device stuck in his ear.

He looks at me grimly. “You need to get permission. See that man over there? He’s the conference organizer. Ask him. Everything goes through him.”

I already know Giovani, one of the producers of this momentous gathering and of all the speeches, music, schedules and food that go with it. So it’s no problem getting permission. When I return to the uniformed policeman a few minutes later, he leads Heather and me through the double doors into a storage area where many travelers to the conference are leaving their bags for the day. As I walk in the room, I’m thinking like a cop or a terrorist. This would be the perfect way to smuggle a bomb into City Hall in a suitcase or a backpack. The policeman closes the door behind him

“Here’s the score for Escomb Prayer,” Heather says as she lays it on top of a pile of suitcases. “Why don’t I sing it through. It’s in the key of D, if that helps.”

“A little,” I say as I get out my chart of Western keys.

As Heather sings in clear and heart-felt tones, I stand next to her, reading the score. Let’s see, my ro is your D, my rei is your G. It’s got two sharps, C and F, my hi chu meri and rei meri.

Heather circles back to the beginning, singing it over and over as I get used to the melody. As my anxiety about finding the right note decreases, I listen to Heather’s words.

As the rain hides the stars;

As the autumn mist hides the hills;

As the clouds veil the blue of the sky;

So the dark happenings of my lot

Hide the shining of thy face from me.

Yet if I may hold thy hand in the darkness

It is enough since, I know,

That though I may stumble in my going

Thou dost not fall.

I am touched by the nakedness of the lyrics and how beautifully Heather brings her passion and vulnerability into it. The prayer reminds me of why I am more Christian than Buddhist. It speaks to that part of me that feels deeply connected to others in love, and to the part of me that reaches out for a personal God, for Jesus.

“Is this an old piece?” I ask.

“Yes and no. The basic ideas come out of the Celtic Christian tradition of the Scottish Hebrides. But it was written by Alistair Maclean, a Church of Scotland minister and a Gaelic scholar.”

I realize how much I don’t know about this area of the world. My mind is a box full of puzzle pieces—Celtic, Irish, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Anglican, Scottish, British, Gaelic, and pagan. I have no idea how to assemble them into a whole.

After cycling through the piece over and over, I try out my longer flute. Heather and I agree that it sounds better. But this makes my job more difficult: until now I’ve only translated shakuhachi symbols into Western notation on the 1.8 flute. Luckily, I have brought my tuner to help figure out the equivalent notes on the 2.4 flute. I turn it on, play each finger position on the 2.4, and write down its Western equivalent.

“Escomb Prayer” is in the key of Bb. I know where Bb is on the 1.8 (ri meri), but not on the 2.4. O.K., here it is, in the tsu meri position. Plus, Heather seems to switch keys in the middle of the piece, and then returns to Bb. I’m trying to focus as my nervous mind is going lickety-split. My shakuhachi mentors, David Duncavage and Yoshio Kurahashi sensei could do this in a breeze. There are 700 people out there. Don’t panic. I don’t have a feel for it yet.

“Can you sing it twice more?” I ask Heather as I run through the notes that could fit.

An image from the movie “Star Wars” comes to mind. Luke Skywalker is on a space ship, being trained to use a laser sword. His mentor, Jedi master Ben (Obi-Wan) Kenobi, has let loose a flying robot that swoops and dives around Luke. In a real combat situation, this flying object could kill him. Now, to give him the ultimate test, Obi-Wan places a helmet on Luke and pulls down an opaque heat-shield over Luke’s eyes. He must defend himself from the robot without being able to see it with his eyes. It’s an impossible challenge. But Obi-Wan declares, “Let Go. . . .Trust the Force.”

What is that transcendent “force” for me? I’ve never thought of it in quite this way, but my equivalent must be Ruach, the Breath of God, and the Wind of the Holy Spirit. In Genesis 1, the Spirit was the first conscious movement in creation after an eternity of Void. The Spirit moved before there was light. And later, when Jesus sends the Holy Spirit, he breathes it out. Like Luke, I can trust in the dark. Ruach is the breath of my Holy Thou. I don’t need to see. It is here, within my own breath, if I can let it have me.

I’m embarrassed to be inspired by a movie. But I say to myself, “Let the Holy Spirit play it.” Time is running out. I put aside my notes and listen to Heather’s voice and the sound of the shakuhachi. Gradually, a series of notes emerges from the flute. The sequence echoes Heather’s voice, sometimes running ahead of her, and sometimes dropping back to embellish her beautiful tones. We’ve spent about forty minutes, and at last we’ve found something that may work. But I am still a bit unsure. “What do you think? Should we go ahead? Is it O.K.?”, I ask.

“It’s fine,” she says. “Let’s go.”

Back in the assembly hall, the morning session begins with a 20 minute meditation. Looking up from the silence, I see His Holiness, Fr. Laurence, and the President of the Republic of Ireland, Mary McAleese, on stage together. Fr. Laurence introduces President McAleese by saying that this is the first time in history that a Dalai Lama has come to Ireland, and the first time that a (Catholic) President of the Irish Republic has set foot in (Protestant) Belfast City Hall. When the applause subsides, President McAleese gives an impassioned speech of hope that “The Troubles,” which have left thousands dead and many thousands wounded and maimed, is over. She thanks all those who risk their lives and community reputations to support the peace agreement that was hammered out two years ago.

President McAleese looks over to the Dalai Lama, who is sitting in his gold and red robes, listening intently to her words, occasionally asking his translator for the meaning of a word. President McAleese says to him, “I want to thank you, your Holiness, for the joyful curiosity and compassion you have displayed during your three-day visit to Northern Ireland.” And then she adds, with a smile, “I do hope that you will not be asked here, whether you are a Catholic Buddhist or a Protestant Buddhist!” His Holiness laughs heartily, as does everyone in the hall.

After Mary McAleese has finished, it is the Dalai Lama’s turn. “I have nothing to add,” he jokes.

But then he does share some thoughts, including this challenge. “In a way, isn’t it incredible that people of the same Christian faith should fight with one another? It seems foolish,” he says with his characteristic kindly smile. “If somebody compared Buddhism and Christianity, then we have to think there are big differences, but not between Protestant and Catholic. You and I have more differences than you do among yourselves. But I wish for you that you never lose hope. I can do nothing. The final outcome really lies in the hands of the people of Northern Ireland themselves.”

Everyone rises to begin a ten minute break. The Dalai Lama and his entourage of guards and Rinpoches walk slowly out of the hall. His Holiness moves, as he often does, with the palms of his hands together in a mudra or gesture of prayer and gratitude. As he passes down the aisle, he reaches out to touch the hands of those who reach for him. Everyone is smiling. After the

break, four people who have been personally touched by the “The Troubles” of Northern Ireland step onto the three-foot high stage that has been specially constructed for this meeting.

After His Holiness returns to his seat in the center of the group, everyone on stage shares his or her story. We hear from David Clements of Belfast, whose father was killed when David was a teenager; Mary Hammon Fletcher of Colrain who, as a teenager, was shot in a drive-by shooting and paralyzed from the waist down; Alister Little of Belfast, a former paramilitary and prisoner; and Richard Moore, blinded by a British soldier’s rubber bullet when he was ten years old.

David, a thin man of about forty, tells us, “On Dec. 7th, 1985 at 7 pm, there was a ring at the gate of the police station. Daddy was about to go home, but he went to answer the gate first. When he got there, the IRA struck, shooting him twice in the head, killing him instantly.”

David has a Bible open on his lap. “I want to read to you from Psalm 10. On the day that my father was killed, we found that his Bible was left open on his desk to this Psalm. We assume that he had read this for his daily devotions that day.

Our enemies sit in ambush in the villages; in hiding places they murder the innocent. Why, Oh Lord, why do you hide yourself in times of trouble?

As David speaks and wonders about God’s justice, I feel shaken and afraid for him and for the people of Belfast. Human beings are so fragile, violence is so close. Yet, throughout his talk, echoes of the Escomb Prayer circulate in the empty spaces of my understanding as I silently blow a steady airstream through my lips and inwardly sing, The dark happenings of my lot hide the shining of thy face from me.

Mary Hammon Fletcher is a beautiful, well-dressed woman of about 40, seated in a wheelchair. She tells us how, in October, 1975, when she was 17, she was shot and paralyzed when she walked out of a movie theater. At one point she stops to cry, and then adds, “I’m not normally like this—it must be the presence of the Dalai Lama. I don’t really dwell on what happened. It happened. I try to get on with it. You have to deal with a wheelchair, and it’s a pain. But I don’t feel different from others. I went on to school and now I work at the University of Ulster in the Department of Diet and Health. I am married now, and have a wonderful husband and daughter. We need decent, honest people to lead us. So, I thank you, His Holiness, and all of you for being here.”

As Mary concludes, I realize that there are tears in my eyes. As I look around, I see many wet cheeks. Mary says she almost never cries, but she allows it in the presence of the Dalai Lama. I can understand Mary’s reaction. Throughout the talks, His Holiness leans in his chair toward the person who is speaking. Perhaps he is trying to understand their English words, but there is more. His face is soft and radiant, and it is obvious that he is giving his complete attention to each person and to the place where our frail humanity meets the compassion of the Buddha. It is remarkable to me that people who know nothing of Buddhism feel held in such tender regard by His Holiness. They sense safety and understanding in his presence. It doesn’t seem to matter that they are Christian and he is Buddhist, or that they believe in God and he doesn’t.

Listening to Mary, I hear again the refrain of Escomb’s Prayer, Yet if I may hold thy hand in the darkness, it is enough.

And I wonder whose hand I’m reaching for now. Is it Jesus’s hand? Buddha’s hand? Or is it someone in the flesh that I love. My wife? Our daughter Rebecca who died prematurely a few years ago? My grandfather? My mother? The Divine Mother? Jesus said that his words were not his, but Abba’s, God’s. To hold his hand is to hold God’s. And I suppose that to be held in Buddha is something eternal too. I feel both as a chain of connections. God’s hand in Jesus’ hand, and Rebecca’s hand in Christ’s hand. Sometimes we need to touch the higher power in the flesh. Who is the higher power who can acknowledge our fragility and the world’s injustices, and not lose hope? Right now, it seems that many people here feel that embrace in the disciplined tender regard of the Dalai Lama. He seems to hold the immensity of these Irish sufferings with an open heart. Perhaps Mary sees that presence in His Holiness. Perhaps, after today, her lovely, courageous self will be even more fully expressed.

Alister Little sits in the semi-circle across from Mary. A man in his late 30’s, he speaks from his chair, telling us how he joined the Protestant paramilitaries at age 14 and was soon arrested and sent to jail for 13 years. He tells an angry, sad tale of a wasted life that he is trying to redeem. And everyone laughs with him when he says with a self-effacing smile, “I thought that God was Protestant.” While in prison, Alister hears of the death of IRA (Catholic) militant Bobby Sands. The Protestant guards are happy, but Alister has a sudden realization.

“Listen, I despised what Bobby Sands stood for. I would have tried to kill him and I bet he would have tried to kill me. But I objected to those guards’ laughter, and told them that it wasn’t right to laugh. I surprised myself. Suddenly I saw Bobby Sands’ courage. I saw that he was a human being. Until that moment I had demonized him. Until then I didn’t consider a certain individual, like a Catholic, to be a person. I didn’t consider their families and the consequences of violence.

“But suddenly I saw Bobby as a person. I saw his pain and loss and that it was the same for him as for me. That moment changed everything for me.

“After my release I was determined to get a vocation in the community, to redeem myself. Now I’m a counselor, working with prisoners and their families. But I want to tell you that there is no inner peace. I have not found that. That’s the price you pay for being involved in violence.”

Alister stops, looks down for a minute, and then wipes his eyes with a handkerchief. The hall is filled with silence. Again, I look around and see tears in many eyes. This is a moment when the veil between earth and heaven seems very thin. Why? Perhaps it is the natural awe we feel in the presence of someone who has turned to face the worst about himself, the worst about all of us.

Alister’s decision to live differently reminds me of the Twelve-Step program for recovering addicts. In the middle territory of the Steps we admit our self-destructiveness and our implicit or manifest violence toward others. The violence here in Northern Ireland is a glimpse into ourselves. Can I stop running from myself and “make a searching and fearless moral inventory of myself?” Can I “admit to God, to myself and to another human being the exact nature of my wrongs and humbly ask God to remove my shortcomings?” Can I get really specific and “make a list of all persons I have harmed, and make amends?” Can I then change my life so that I awaken to the violence in myself and admit the harm that I might cause others and myself each day?

How many of us can live these principles? It seems nearly impossible. And yet, if we don’t do this, how can we ever live peacefully in Northern Ireland or anywhere else? As the Dalai Lama has told us several times in this Buddhist-Christian conference, true peace begins in the individual heart, in Alister’s heart and in mine. As a Christian, it seems to me that only if I can take responsibility for my own violence and peace, only then can I glimpse the face of God. Only then can I glimpse the secret of Escomb’s Prayer, The dark happenings of my lot hide the shining of thy face from me.

Richard Moore is seated next to the Dalai Lama. “I am blind.” he says with a slight smile, as he looks straight ahead across the semi-circle of speakers, “But I can see better now. I asked the Dalai Lama if he’d tell my wife that.” Laughter swells across the hall as many of us turn to one another, enjoying Richard’s quick vulnerability and humor.

“I have spent two days with the Dalai Lama and I feel we are friends. At least that’s what I am telling my friends back home.” More laughter.

“On May 4th, 1972 I was ten years old. A conflict had arisen on the streets. I joined in by throwing a rock at some British soldiers. Being more afraid of my parents than the army, I ran past an Army lookout post with a rock in my hand. A British soldier shot a rubber bullet, destroying my right eye and blinding me in the left one. I know you’re thinking that’s horrific, but I accepted it. It was easy to accept. I don’t know why except that there was a godly influence there. I cried that night because I’d not see my mommy and daddy’s face again.

“I thought, ‘Nobody is going to treat me as a blind person. Nor will I be seen mixing in those circles.’” Richard’s smile again invites us to laughter.

“But that is what helped me and gave me strength. That spirit of acceptance. I feel that the Dalai Lama understands this.” Richard turns to His Holiness and holds out his hand toward him. Without hesitation, His Holiness reaches out and squeezes Richard’s hand for a moment.

Then Richard adds, “Recently I visited Bangladesh. Standing there in the dirt on a busy street corner, I thought, ‘There but for the grace of God, go I.’ Northern Ireland isn’t such a bad place after all. If everyone could see this level of poverty and suffering, I thought, they’d realize, ‘What the hell are we fighting for?’ I’d rather be blind in Northern Ireland than be able to see in Bangladesh.

“For a time after the shooting, my mother thought perhaps that prayer could cure me. She was always at church, praying. She had me wearing sacred medals all over my clothes, and would often rub holy water on my eyes, from four or five different holy wells in Ireland. And I remember somebody saying, ‘You’re lucky you didn’t drown’.

“Now, I’m married with two children. I was there the day that both were born, but I couldn’t see them. They had their first communion. And I would have given anything on earth to have my sight. And then on Christmas morning, I’d give anything to see their faces. So there is a price to pay. But I don’t allow the negative emotions to steal me.

“My daddy once said, ‘Never let one cloud spoil a lovely day’, and I believe that.”

As I listen to Richard, I realize that his sincerity, wisdom and humor have me crying and laughing at the same time. In fact, every speaker has embodied these qualities. What kind of beauty is this, that includes what is most horrid and ugly about human beings? I think it’s the kind of beauty that Christian sculptors and painters have tried to express for centuries in their depictions of the Crucifixion. Somehow, in that moment where all love, kindness, and hope disappear, an even deeper, more inclusive love and hope appear. Resurrection inside Good Friday. I’ve been a Christian all my life, so it’s not surprising that this unlikely juxtaposition feels so deep in me, as if it is the bedrock of my identity. To express it with the shakuhachi is my highest aspiration. I think that I will never have the technical skill of someone like Yoshio Kurahashi, Yo-Yo Ma or Itzak Perlman. Never. But maybe there is a small hope that I, as a Christian, can one day express in just one note the universal human experience of love’s death and resurrection. Then, I could die, feeling complete about my life.

Now, all seven hundred of us are scheduled to join in another 20 minute meditation. As the stories of our guests stir in our hearts, Giovani, an associate of the World Community for Christian Meditation, introduces the silence. “Feel the weight of your body on the chair,” says Giovani quietly. “And feel, too, the earth beneath that is holding you up, supporting you.”

Giovani has named something for me, perhaps for all of us. In their vulnerability, humor, and courage, our speakers have expressed their willingness to trust in the basic goodness of things, even when we are overwhelmed with the injustice of what human beings can do to one another. In the silence of breathing, one breath at a time, I think of my medieval mentor, the Dominican friar Meister Eckhart who wrote “Expect God evenly in all things.” All things. How difficult this is, but how beautiful and inspiring to be in the presence of those who live this truth.

Heather and I come forward. We stand at two different microphones under two different spotlights near the stage. I blow a first note out into the chasmal, silent hall. It is a long breath, a long note, testing my ability to stay with all the contradictory feelings that have been stirred up in listening to these stories. Can I stay with the truth that I’ve been given for at least this long, from the beginning of this breath to the end? Can I let the courage of David, Alister, Mary, Richard and His Holiness be so within me that they play this note?

The next full breath flows into me like a tide from the nearby Irish Sea. With the out-breath I begin a little riff of notes to introduce Heather’s melody. Her voice slides into the midst of the shakuhachi notes and we sing together for a few lines. In the middle of the prayer, the shakuhachi disappears so that only Heather’s voice swells out from that deep Irish wellspring of hard-won hope, Yet if I may hold thy hand in the darkness, It is enough since, I know. . . The phrase repeats itself within me and each tear that drips down sings out, “I know, I know, I know”, as if it is coming from somewhere beyond.

What a strange gift it is, to glimpse the dawn that is already coming from deep within the terrifying nightfall. In my body I feel the spontaneous courage of children who seem born with the song, though I may stumble in my going, Thou dost not fall. Thou dost not fall.

© Robert A. Jonas, 2006-2023 (reprint by written permission only)