image © Heather Ray

On Saturday evening, December 12, 1998, I sat on a school bus with forty other pilgrims as we pulled into the village of Bodh Gaya in India’s Bihar Province. It had been ten hours since we left Varanasi. We’d rolled past hundreds of miles of flat, hazy fields, past countless stacks of hay looking like small cottages in Van Gogh paintings. Farmers walked slowly behind gray oxen. Women in bright saris bent low to tend the rice fields. Naked children played in the dirt near huts made of stone, mud and straw. We’d passed a constant stream of big trucks festooned with Hindi script and paintings. This was the main road to Calcutta. The trucks were carrying grains, vegetables and fruit from these fields to feed the city’s nine million hungry residents.

“I can’t believe it,” someone said. “I feel as if we’ve traveled back into prehistoric times. The trucks used to be elephants–that’s the only thing that’s changed.”

We were Christians and Buddhists from the United States, Canada, Ireland and England who had come to participate in a Buddhist-Christian dialogue with His Holiness, the Dalai Lama of Tibet. We wanted to come to this place where, 2,500 years ago, Siddhartha Buddha sat all night under a tree to make his greatest spiritual effort. According to legend, his mind and heart opened into the infinite at dawn. A descendent of the tree, called the Bodhi Tree, still grows from this sacred spot where Buddha was Enlightened.

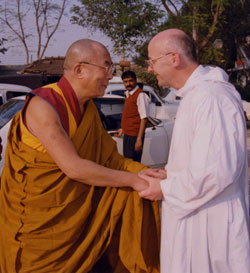

I was excited to be part of this historic gathering, led by the Dalai Lama and Fr. Laurence Freeman, a Benedictine monk and priest from London. Laurence was the spiritual leader of the World Community for Christian Meditation, one of a handful of international organizations dedicated to the Christian contemplative path. I had been reading Fr. Laurence’s work for years, ever since Margaret and I met him at a retreat in Montreal in the early 1980’s. At that time, he had just been selected to lead his small community after the untimely death of its leader, Fr. John Main, a contemplative priest who had studied meditation in Asia and had been a friend of the Dalai Lama. Fr. Laurence soon befriended His Holiness as well, and in the mid 1990’s they envisioned a series of three Buddhist-Christian events called The Way of Peace, to be held in India, Florence, Italy and Belfast, Ireland.

When I heard about the series six months before, I immediately signed up for the Bodh Gaya trip. Of course, I wanted to meet the Dalai Lama. But I was also eager to meditate and to play shakuhachi in the most sacred of Buddhist pilgrimage sites. After reading several of Laurence’s recent books, it had became clear to me that Laurence had a better grasp of the common ground between Buddhists and Christians than anyone else I knew. I wanted to learn from him about how to integrate Buddhist meditation in my Christian life. When Fr. Laurence discovered that I played shakuhachi, he invited me to play as an introduction to some of the meditations. Of course I jumped at the chance. I brought two shakuhachis with me from Boston, one short and one long, in my backpack.

I had no regrets about my decision to come, but after a week in Delhi and Varanasi, I felt shaken by the level of poverty and pollution, and by the sheer numbers of people. India’s population was approaching one billion, and sometimes it seemed as if they were all on the roads. I had never witnessed so many beggars on city streets or so much filth. Men peed on the roadside, and everyone threw wrappers, bags, garbage and junk into the thoroughfares. At the edges of town, the fields were dumping grounds, covered with layers of plastic bags, broken bottles, scraps of paper and cloth and rotting food. Along the roads, “untouchables” swept the continuous rain of garbage into little piles that the nearest vendors burned where they were, to keep themselves warm or to use as fuel for their breakfast fires. The air was always thick with smoke from the fires and from the clouds of dust kicked up by all the people sweeping with their brooms.

Meanwhile, it seemed that all Indian vehicles–trucks, cars, rickshaws and scooters–were engaged in a desperate struggle for survival. Drivers raced down the middle of the road at breakneck speed – there were no painted lane markers, no posted speed limits – swerving away from oncoming traffic at the last second. And the traffic was heavy, for the roads were cluttered not only with vehicles of every sort, but also with cows, donkeys, and dogs. The animals ambled casually into the openings between cars and seemed eerily adept at avoiding collisions. When a clear space opened in front of a car, the driver floored the accelerator and kept it floored, tearing helter-skelter down the road and honking all the way. A cow in the road just twenty yards ahead nonchalantly stepped aside, avoiding instant death without even breaking a sweat. It was like a big game of chicken. If you were a Westerner used to order, rules and common courtesy, forget everything you thought you knew about safe driving.

On the roads of India, everyone honked his way through the chaos and the ever-present cloud of pollution. Almost all drivers lay on the horn constantly or in a rhythm of short blasts that added to the perpetual sense of urgency, as if getting somewhere fast mattered. Where could you go that wasn’t exactly like the place you just left? It seemed to me that for ninety-nine percent of the people, timeliness really didn’t matter. Nothing happened on time anyway, so what was the rush? Aside from the frenzy on the roads, the people I saw were either walking slowly, looking around, gabbing with friends, examining a vendor’s wares, and waiting for a sale in the sun, or they were bending over, moving rice plants into or out of the ground. I had the sense that in this country nothing really changes. I knew this was a stereotype, but still, it seemed that everyone repeated what they’d been doing over and over until they simply died. I was fascinated, but also overwhelmed and sometimes scared. I was grateful for this little island of safety–an air-conditioned bus, accompanied by other Americans and two local guides–in a sea of smoke and suffering.

Now, the fields gave way to clusters of buildings and roadside shops. Up ahead, in a grove of trees, I glimpsed the head of a giant statue of the Buddha. It seemed to waver as the heat of the fields flowed upward around it. Across the aisle, someone said, “I’ve heard about this statue. It’s 125 feet high, built by some wealthy Japanese Buddhists. They have a temple there, as do lots of other Buddhist sects.”

Kevin, the 65 year-old Jesuit priest who once worked here as a missionary, turned around and added, “Everything happens around the Bodhi Tree here. It’s the center of gravity. Of course, it’s not the actual tree, but probably a scion of the original one. Since it’s such an important destination for Buddhist pilgrims, investors have figured out that there’s money to be made. So there are new hotels, monasteries and businesses going up all the time. A lot has changed in the fifteen years since I was here. But all around these new developments, nothing has changed for the local people.”

The talkative person behind me was Tom, a tall, wiry guy from Columbia, Missouri. He was one of the half-dozen Buddhists on our bus. Since he’d been to Bodh Gaya twice, everyone around him, including me, peppered him with questions. For the last hour he had been holding forth on theological and philosophical topics such as sunyata and kenosis with two other young fellows. I listened in occasionally, but found Tom’s approach too abstract and intellectual for me. And anyway, I was absorbed with the sights that flowed by our windows. My eyes must have been permanently opened wide as I stared at everything and everyone, trying to understand what I was seeing. When Tom fell silent for a moment, I turned around and asked him, “Can you tell me something about the economy here?”

“Bihar Province is the poorest in all India,” he said. “It’s got the lowest literacy rate, about 1%. So don’t expect to see any newspapers. They have a landlord system of agriculture that has been here since before the British came in the 17th century. And, unfortunately, independence didn’t change anything. Almost everyone works in the fields all day. Some wealthy landlords own most of the land. They charge high rent to the peasants and also sell them seed at exorbitant rates. The 1947 Constitution was supposed to bring democracy. It outlawed the caste system. But in reality the caste system is as strong as it ever was. The underclass, called Dahlits or Untouchables, does all the menial labor and never has a chance to get ahead.”

As other people asked Tom about the region, I noticed that our bus had come to a stop on the road. Some of us stood up to see what was happening. We were completely blocked in by large agricultural trucks on both sides. How did we get into the middle of this jam on a two-lane dirt road? It was impossible to tell. Our bus driver sat calmly, as if this were normal traffic. But outside, truck drivers stepped out of their vehicles. Some were obviously upset, shouting and waving their hands as they looked ahead on the road for an opening. Others stood around in groups of three and four, smoking cigarettes and talking calmly. Finally, the word came back from our driver that these stoppages were commonplace. He suggested that we get out of the bus to pee in the bushes by the side of the road. I stepped out, wandered along the road for about 20 yards and found a large bush to hide behind.

After a half hour, the driver shouted, “Let us go. Things are beginning to move!” I hadn’t noticed any change.

Back in the bus, I was surprised to see our driver start the bus and begin moving forward, even though none of the trucks hemming us in seemed to move. He was attempting to drive through such a small gap between trucks that the interior of the bus grew dark as the tall sides of the trucks slide past our windows on either side. A slight metallic sound grew louder and louder as we crept forward, and I realized that the metal side-panels of our bus were scraping along the sides of the surrounding grain trucks. Still, the driver and our guides seemed unperturbed. Soon, there was more space on both sides and our speed increased. We had made it through the logjam. Clearly, the driver was determined, and experienced in finding the slightest glimpse of light in a maelstrom of people and vehicles. I could feel claustrophobic in a country like this, always hungry for elbow room. To survive, I’d have to learn how to spot those openings and not to hesitate.

Someone asked Tom, “It sounds as if this region is politically volatile. Is it dangerous for us?”

Tom responded, “Hard to say. The wealthy have their own militia, in case the peasants get out of line. One of the wealthy landowners around here is a Member of Parliament. Everyone knows that he is responsible for eighteen murders a few years ago, but no one does anything about it. On the other hand, the local Maoists have also gotten powerful. Occasionally they will murder an upper class person to demonstrate their power. Then there are reprisals.”

“Doesn’t sound safe to me,” someone said.

Tom laughed, “No risk, no adventure. Actually, things have been quiet recently. But it’s good to be careful. You probably don’t want to go out alone at night. We’ll be staying at the Root Institute, a Tibetan retreat center very near the Bodhi Tree. A few years ago, a gang broke into several cabins and robbed some pilgrims. They shot three of them in the legs. So the Institute built a twelve-foot high concrete fence around the whole complex of buildings. They have guards posted as well, so I think we’ll be fine.”

“How ironic,” the woman across the aisle, Janet, said. “I mean, in this place where Buddha found ultimate peace and wisdom, that there would be so much darkness and violence.”

“That’s true,” I observed. “But then, it makes sense, actually. Buddha’s approach was to sit down right in the middle of our problems and worries and to find peace exactly there. He didn’t think you could find peace somewhere else. It’s always right where you are, even in the ugliest of times and places. Gandhi, Mother Teresa and Martin Luther King all had that attitude. It’s a non-violent response to suffering, to accept the pain without striking out or leaving.”

“Well, you’re right,” Janet replied, “I know the Dalai Lama sees it that way. He’s committed to meditation as a powerful non-violent response to the Chinese invaders.”

“Ya.” The man in front of me, Larry, turned around to join the conversation. He was the 55 year-old owner of a construction company in Indianapolis. We had already talked, so I knew that he had strong opinions about meditation. He was convinced that it’s a powerful spiritual tool that should not be uprooted from its ancient traditions.

“When the Dalai Lama meditates, you know it’s not just for relaxation. He’s not some New-Age type doing it for relaxation while he sips a mocha latté.”

Carl, a big Roman Catholic man from Minneapolis had been my seat-mate on the bus. Soon after we sat down, we traded stories about why we came to India. When I discovered that Carl, who is in a Christian meditation group at his church, loved the writings of Henri Nouwen, I gave him one of the two copies of my book about Henri that I had brought along on the trip. He’d been reading it silently for hours. Now, having read the whole sixty-page Introduction he wanted to talk. We soon discovered that we were both football fans and that our favorite teams, the Minnesota Vikings, and the Green Bay Packers, were arch rivals. He found this hard to believe, that he would be sitting next to a Packer fan.

“How strange,” Carl exclaimed, “Wasn’t that you who played a flute for the Eucharist in Varanasi? I’ve never heard anything like it. Such a haunting sound. But how does this fit together?” He laughed with a big booming outburst. “I mean, what’s the likelihood that I would come to India and be sitting next to a writer who knew Henri Nouwen, who is also a Packer fan who plays a Buddhist flute? It’s incredible.” We enjoyed a good laugh.

“Well, I guess it is unusual,” I admitted. “But from the inside out, it all makes sense. When I was growing up in the 1960’s, the Packers were a religious experience. Vince Lombardi, Ray Nietsche, Jerry Kramer–they had a spiritual dedication to the game, brought along from their Christian beliefs. They were so aggressive, but they had some kind of inner discipline, to channel the anger in precise ways.”

“Ya, you’re right. I’ve put my VCR on slow motion. Watching a football game is like watching a neatly choreographed ballet. You see the precision in their bodies.”

“It’s like the martial arts,” I added. “You train your body as a precisely calibrated machine. But of course football has changed since the 60’s. It’s so much more about televised games and money now. In my childhood, football was all about America to me, about the democratic melting pot, Whites and Blacks on the same team, and a Godly vision of a community that values fair play, doing your best for the team and then shaking hands with the competition at the end.

“So I have this vision, Carl. It’s been cooking in me for the last year or so. I want to play the National Anthem on the shakuhachi at a Green Bay Packer game.”

“Oh my God, oh my God!” Carl cried out, as he banged the wall of the bus. “That’s so good. East and West, Buddhism and Christianity, art and martial arts, Vince Lombardi and the Buddha. You’ve got to do it!”

Carl’s response astonished me. I’d been barely conscious of the dream of the shakuhachi at a Packer game, thinking of it as a fantasy, as a possible scene in someone’s movie. But hey, maybe it wasn’t so weird. I just wished there were a Japanese Buddhist on the Packer team. That would make the connection more appropriate. Two years later I would come close to this kind of inter-cultural, artistic drama in Boston where I would team up with the Japanese artist and opera singer, Kaji Aso. I was already learning to play the National Anthem on the shakuhachi, and soon Mr. Aso and I would rehearse this song so that we could play it at Fenway Park when Japanese players would pitch. Unfortunately, Mr. Aso would die in 2006, so that dream was never realized.

I still sensed the presence of the 1960’s Packers within me. I was never big enough to play professional football, but sometimes I felt a Lombardi-like dedication to the shakuhachi. I wanted to blow each note with the same meticulousness and religious fervor that Lombardi put into each execution of the famous Lombardi sweep: Be fully awake at the snap. Suddenly, Bart Starr barks, “Hut, hut”, pivots swiftly like a fisher cat pouncing on a mouse, hands off to fullback Jim Taylor just as Taylor passes by at full speed and flows into the wake of pulling guards Jerry Kramer and Fuzzy Thurston who open a wide corridor through the Dallas Cowboy defenders in a bitter cold blizzard at Lambeau Field. Boy, if I ever composed my own music on the shakuhachi, the Packers would be part of my song.

The Root Institute stood like a small, walled and guarded medieval hamlet in the middle of the vast rice fields surrounding Bodh Gaya. Having walked through the enormous concrete walls and gates, and having registered at the administration building, I was happy to find that my roommate was once again the Irish singer-songwriter, John Drury. We had roomed together in Delhi when we arrived, and we had taken an instant liking to one another.

“Oh, this is grand,” John said, as we made our beds. “It should be an interesting group. Our forty pilgrims are blending with another forty who have come from a tour somewhere else in India. I’ve already seen a woman I knew in Calcutta, a Baptist minister.”

“A Baptist?” I was incredulous. “A few Baptists come to the Empty Bell from Old Cambridge Baptist Church. It’s unusual, but after all, that’s Cambridge, a really liberal community. Outside of Boston, I don’t know. I’ve been going to public Buddhist-Christian dialogues for almost fifteen years, and I’ve never met a Baptist at any of them.” Maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised. The B-C conferences in America used to be all Roman Catholics, but in the last few years I’d met several Lutherans and Methodists. They always added a fresh perspective to the contemplative dialogue.

“Well, Connie is great. She and her husband have been missionaries here in India for twenty years. They’ve found a way to integrate their Buddhist meditation with the Bible. Did you see Fr. Laurence at registration?”

“No, why?”

“Well, he says he wants us to do the music at the sittings each day. We can do some more duets. Laurence is hoping that you’ll play shakuhachi for the first meditation at the Bodhi Tree this morning.”

“Great, I guess. With the Dalai Lama there, I might be nervous.”

In Delhi, we had stayed at the Sri Aurobindo Ashram. There, I learned that John was a father of three children, a 47 years old guitarist, singer and songwriter who used to work at the L’Arche house for the handicapped in Calcutta. Though he had a thick Irish accent, he’d been living in West York, England for years. John had worked at L’Arche when Henri Nouwen was the pastor at a sister community called Daybreak in Toronto, so he knew Henri and his writings. In fact, John attended a L’Arche retreat that Henri had led in Ireland. My new friendship with John helped me to feel at home in this strange land. The two of us stayed up late that first night in India, discussing music, Henri, meditation, working with handicapped people, and fathering.

John felt that he was at a creative edge in his two life interests–how to improve the conditions for handicapped people around the world, and how to create new music. I’d listened to his album, Michael is Leaving Las Vegas. I found it to be lovely, lyrical and romantic. Sitting on our beds at the Ashram, we had had fun experimenting with his guitar and my flute. I had never done improvisation before, and while I felt clumsy trying to find notes and progressions that worked with John’s guitar chords and songs, I enjoyed the collaboration immensely. Departing from my Buddhist Sui-Zen repertoire made me nervous. My only experience with Western musical notation and scales was over thirty years old, but I realized that I must learn how to do it again. Could I learn to move easily between Japanese honkyoku and Western music, just as easily as I could sometimes move between Zen meditation and charismatic Christian hymns? Teaming up with John in Varanasi a few days before, I had had my first chance.

Our group was staying in the Hotel de Paris hotel, a once-famous British hotel. On Sunday morning we walked up the road to the recently refurbished “Ideal Tops” hotel to host a Eucharist for our group and any Christians at the local hotels. Our room turned out to be an unfinished lobby with several carpenters and electricians moving around silently in the background, occasionally pounding something into a wall or door, and then stopping to watch us silently: their dark faces looking at our White ones. At Fr. Laurence’s invitation, John and I improvised a short piece with guitar and shakuhachi for the Eucharistic meditation. It was the first time that I’d improvised in public. I was pleased to have taken the risk and to hear from two people afterward that our playing was “really beautiful.”

After breakfast on our first morning in Bodh Gaya I walked with eighty fellow pilgrims out to the road to two buses for the ten-minute trip into town. People referred to our destination as “the Stupa,” the stone tower beside the Bodhi Tree and the acres of temple grounds surrounding the Tree. We passed a few small houses with goats in the yards. Behind the houses rice fields stretched into the distant haze. Along the last half-mile of our approach we saw new roads with new concrete and stone monasteries. Nearing the Stupa a stream of people walked on both sides of our bus past makeshift roadside stands where vendors sold food, clothes, sacred objects and souvenirs.

As our bus pulled into a curb on a tree-lined boulevard, someone pointed out the high iron fence surrounding the Stupa grounds. In Delhi, Fr. Laurence had told us that the local authorities would close the Stupa to other pilgrims during the days of our Buddhist-Christian dialogue. They felt that security for His Holiness would be too difficult otherwise. Apparently, a breakaway faction of Tibetan Buddhists had put out a contract on the Dalai Lama’s life. And of course, the Chinese wanted to see him dead. Guards with machine guns stood along the curb and every fifty feet beside the iron fence. As we climbed down from the bus we were instantly surrounded by men and women in loose-fitting cotton saris, all encouraging us to buy their wares. Tibetan vendors were everywhere, selling holy thankgas, cloth icons that one hangs on a wall, statues of the Buddha, incense and Tibetan singing bowls. The smell of fried dough, cinnamon and something like garlic filled the air. The small fires of the vendors were already creating a thin haze of smoke that hung above us, almost blotting out the sky. Scores of Tibetan monks walked in small groups. Some of the monks wore white respiratory masks.

As we stepped up onto the wide stone pathway that led round to the main gate of the Stupa, hundreds of pilgrims, five or six people deep, lined our path on both sides. We were being led through the middle of this crowd by the local police and Indian military. People held prayer beads, spin prayer wheels, and mutter silent prayers, as they stood still, looking out from wind and sun tanned faces. Most were expressionless. As we walked slowly I looked into the eyes of red- and orange-robed Tibetan monks and old men and women who had come down from the north, from Dharamsala, Lhasa and Khatmandhu, to see His Holiness. I felt the guilt of White privilege. How is it that we were chosen to be close to this holy man? Really, I should have given up my place to that old Nepalese man there, or that young Tibetan mother there.

I silently repeated my favorite short prayer and mantra, “Help me”, over and over, with each breath as I looked guiltily at people’s faces. I saw no reason why I should be here, but maybe God did. God sees from the largest possible perspective. Maybe God would help me understand what to do with the precious gift of being here, in the most holy of Buddhist places on earth.

As we turned the corner into the wide, sloping stone entryway that descended to the Stupa gate, my ears rang with the pulsing beat and high-pitched cacophonous singing voices coming from the boom box of a street vendor. I was shocked and distressed to find, in this holy place, such a carnival atmosphere. This, of all places, should have been suffused with the meditative tones of Sui-Zen. I felt angry, thinking of how Jesus overturned the tables of the money-changers who had set up shop at the gates of the temple.

After about one-hundred feet, we came to a semi-circle of security men and women who blocked our way. His Holiness was on the inside of the circle, by the main entrance, just twenty feet from us. He was of average height, clothed in bright orange and yellow robes, just like the other monks who surrounded him. Someone told me that these were geshes and lamas, Tibetan spiritual leaders who the Dalai Lama had brought along to learn about Christianity. His Holiness wore tinted glasses in the bright morning sun, and showed a radiant smile as he shook hands with some local dignitaries.

Now, Fr. Laurence walked briskly down the entryway behind us, the long white robes of his Benedictine community fluttering in the breeze of his quick, steady stride. Our group divided so that Laurence could walk by us to greet His Holiness. Both he and the Dalai Lama were smiling broadly as they came together. First they stopped to bow slightly to each other, each one bringing the palms of his hands together. Then they hugged in a warm, full-bodied way. Smiling, they embraced for at least five seconds as the eighty people in our group and the Tibetan monks and security guards watched. Then, with their heads still touching, they spoke softly, out of our hearing. Even though I couldn’t hear what they were saying, they looked like they were thoroughly enjoying each other’s company.

When Laurence and the Dalai Lama went into a small ticket office to talk, the security guards who were dressed in Western style suits and ties, asked us to line up, men in one line, women in another. Two lines for men, two for women. At the head of the men’s line stood two burly Tibetan guys and at the end of each women’s line stood a young Tibetan woman. All had small walkie-talkies strapped to their sides. Behind them, between the last gate to the Stupa and us, stood men in pea-green army uniforms with sub-machine guns slung across their bellies, watching. One by one we were frisked for weapons.

I was used to being checked by the security people in airports. But this frisking was much more detailed. Each arm, the back, the buttocks, feet, ankles, legs and crotch were touched, searching for a hidden bomb, pistol or knife. When the security man briefly grabbed my balls and penis through my pants I realized that the level of threat and danger was higher than in any other situation I’d experienced. As far as they were concerned, I could have been a eunuch with little grenades attached to my crotch. Were my balls the real thing? I felt the impersonality of the situation intensely. These guards had no idea of who I was or where I had come from. I was merely an alien, potentially strange, body. After our search we were asked to stand on either side of the final staircase to the sacred temple, waiting for Laurence and His Holiness. But in our wonderment, our group covered the stairs completely with bodies and excited talk.

When Laurence and the Dalai Lama came out of the ticket office, they were smiling and holding hands with each other. Again our group parted to let them pass. We had been told by our organizers that we were not to speak with the Dalai Lama when he walked by. Nor were we to take pictures of him without permission. I was a photographer, and because of my years of involvement in the Buddhist-Christian dialogue, I had many questions for the Dalai Lama, but I was not here to have my personal needs met. Mostly, I was here to listen as Fr. Laurence and the Dalai Lama engaged in dialogue. Each day I would be playing shakuhachi for the assembled group, and I felt thankful to have this one area of active participation.

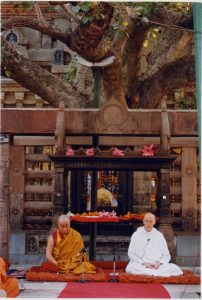

Laurence and the Dalai Lama then led us down more stone stairs. As we descended, I looked across the four-acre grounds where many altars, statues and walkways surrounded a one-hundred foot high temple that was shaped like a tall, narrow pyramid. At the bottom of the twenty-five feet of stairs we walked to the base of the fifty-foot wide pyramid, and then around it to the other side where an area for sitting had been arranged under a large tree at the base of the pyramid. That would be the Bodhi Tree.

I tried to get my mind around this moment. Right here is where Siddhartha’s mind and heart opened to the Unconditioned. And yet, I was struck by the ordinariness of this place. It was not a Westminster Abbey, a Chartres or a Vatican City. Just an old tree with a cheap concrete fence around it. One might have expected all the ground beneath the tree to be carefully sculpted in stone terraces, perhaps composed in levels to reflect the hierarchies of Buddha’s cosmology. But on the ground was nothing but dirt. Dirty, unkempt dirt. Actually, I was glad for it. My favorite Buddha statues were the ones that show him at the moment of Enlightenment when he touches the dirt with his right forefinger to express his realization that the Earth itself is his witness. As if the earth were a subject, a presence who could witness.

Within the concrete fence surrounding the tree I saw another small fence, this one an elaborately carved gold-leaf enclosure given by the Sri Lankan government. The tree itself stood fifty feet tall, its big barrel trunk and leaf-heavy branches extending out thirty feet in every direction. Having been instructed to bring something to sit on, we all spread out our blankets and towels on the dirt. Most people would be in the sun, looking into the shade of the tree where Laurence and His Holiness were seated next to one another. I put my blanket down near Laurence’s cushion so that I could play a honkyoku piece from my place when Laurence gave me the heads-up sign. I was happy to be near the Dalai Lama, and happy to be in the shade, where I looked out at the eager faces of our group. And, I felt a little uneasy because I was seated right in front of an Indian guard in camouflage dress who held an automatic rifle at his side.

After settling onto their cushions, Fr. Laurence and His Holiness greeted everyone briefly and then Laurence announced the beginning of a twenty-minute silent meditation. This was my cue. I lifted the shakuhachi and played Daiwa Gaku, Great Peace.

I had looked forward to this moment, to offer a few minutes of pleasure or beauty to this man who worked tirelessly for compassion, reconciliation and world peace. Maybe I wanted him to notice me, as well. I felt embarrassed for the fantasy that he’d like my playing, that he’d even want to be friends with me. Luckily, even in my nervousness, I realized that this was a good place to bring awareness to the jitters. I focused on each in-breath and out-breath. What is this? I silently asked one breath at a time. What is this tension in my belly? What is this embarrassment? What is this constant craving to be “better” than who I am? What is this–wanting to be liked?

In the middle of the piece I blew one note a little longer and with more strength than I should have. The note was supposed to be blown slow and steady, with kyo sui, empty breath, but I wanted to empathize with the Buddha in the last moments of his Enlightenment, when he made that final push through his resistance. I imagined the strength and total focus of that moment and blew strong with some extra sound of wind.

For the Buddha, the inward shape of the false self was like a house in which he was imprisoned. In that decisive moment at dawn, the house caved in. Buddhist scriptures quote him speaking in verse:

Through the round of many births I roamed

without reward,

without rest,

seeking the house-builder.

Painful is birth

again & again.

House-builder, you’re seen!

You will not build a house again.

All your rafters broken,

the ridge pole destroyed,

gone to the Unformed, the mind

has come to the end of craving.

(Dhamapada 153-154)

A few seconds after blowing the last note, Fr. Laurence struck a small temple bell next to his cushion and we entered into silent meditation. Twenty minutes later, Fr. Laurence hit the bell again and turned to the Dalai Lama.

“His Holiness, we come here today, to this holiest of Buddhist places, to learn from you. We seek your wisdom in this time of great trouble and suffering around the world. Some years ago, you and I spoke of visiting each other’s sacred places. Today we come here to learn from you about this place and what the Buddha discovered here. We are here as guests, to ask you, His Holiness, to guide us as pilgrims in this holy place. You have said that you are a simple monk. But, I think you are a very special monk.” Everyone laughed out loud, including the Dalai Lama. Clearly, he could understand some English.

“And in the next few months,” Laurence continued, “you will come to a monastery in Florence, Italy, to hear more of our sacred story. We have this precious opportunity, to share stories of Jesus and Buddha and the rich history of our traditions.”

The Dalai Lama bowed to Laurence and then spoke in Tibetan, pausing occasionally, so that the translator at his side could repeat his words in English.

“Thank you very much. We are honored that so many Christians would come to this place of Buddha’s Enlightenment. We are here, not just to exchange nice words and smiles but to speak heart to heart.

“As we meditate, pray and discuss together, we hope that our common effort will benefit all beings. I can encourage others to go to Sarnath, the place of Buddha’s first public talk after Enlightenment, and to the holy city of Jews and Christians, to Jerusalem, not as mere tourists with a camera, but as pilgrims who seek the truth.

“I am a Buddhist and I do not think that every religion is the same. But I have great admiration for your Christian wisdom. Through many centuries our two paths have offered immense value to people. So I have deep admiration and appreciation for how Christians improve the happiness of humanity.

“Once, I went to Lourdes in France to meditate in front of the statue of Mary, and I drank the holy water there.”

His Holiness paused, looked at Laurence and then at everyone and laughed. “Although the vision of Mary didn’t materialize. . .” Everyone joined in the laughter.

“Still, a feeling arose there. I felt that millions of people come to Lourdes to fulfill their utmost desires and wishes, and this gave me immense joy.

“So, the visiting of different holy places is a special spiritual discipline. I hope that we can make a new example here with my special brother, Fr. Laurence and with you, brothers and sisters. And I also want to show my monks here,” as he pointed to the front row of a dozen Tibetan Rinpoches and Lamas and laughed, “the importance of these dialogues.

“Now, Fr. Laurence, you have asked about the traditions surrounding the Bodhi Tree. But I must confess, though I consider this a very holy place, I don’t know much about its history.” His Holiness chuckled again and rolled his eyes.

“2,500 years ago Shakyamuni Buddha, through his own practice in his lifetime, and through millions of eons of purification, reached the completion of this effort here. Well, we think it happened here!” Again, he and everyone laughed.

“And then other great Buddhist masters like Nagarajuna and many others came here to seek enlightenment but if you ask exactly where” he added as he gestured with his right hand toward the tree and around the grounds, “I don’t know.” More laughter.

“Like Nagarajuna, we can sit here, meditate, and have deep insight. As a Tibetan, I feel proud. All these teachers have blessed this place. With the help of these blessings our true nature appears. Yes, the place itself can help. Of course, common to all the great spiritual traditions is the good heart. This often does not come easily. Some kind of discipline is important. Time is always moving so we must utilize time wisely. Live honestly and truthfully, sincerely, and use the rest of the time for helping others, praying for the benefit of others. One must try to live with respect so that in the end we can say, Yes, I used my brief time helping others.”

He paused, looked across our faces and laughed, “and also for a little relaxation.” Again, the whole group erupted in laughter.

I chuckled too, assuming that His Holiness was making a joke about a subtle kind of attachment that can arise for people on a spiritual path, an attachment to helping others and religious experiences. I assumed that many of us Christians have sometimes fallen into this temptation, so addicted to ministering that we must be in control—never helpless ourselves, never needing to receive the help of others, never relaxing. My wife, Margaret, taught at the Episcopal Divinity School (EDS) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She told me once that the EDS community had designated a small area on the lawn in front of the chapel as a “Ministry-Free Zone”. If you stood in that zone, no one could minister to you.

On his cushion, Fr. Laurence had been leaning toward His Holiness, listening with his eyes closed and then laughing with the others when His Holiness cracked a joke. Now, he sat up straight and added, “I think this is a great gift that you, Your Holiness, and other Buddhists, offer to the world: some practical methods of meditation to encourage a good heart, and to become free of our addictions, even our “good” addictions. We Christians have had our methods of meditation and contemplation as well. For us, our goal in meditation is to let go of our selfish way of seeing so that we can have the mind of Christ. If we say our goal is to become like God, to be transformed in God’s image, this must include all of us–our bodies, minds and spirits. Then we can love as God loves.”

“Yes, yes,” replied the Dalai Lama. “First, the mind must be trained. This is fundamental. Good ideas are not enough. In meditation, we let the natural purity of the mind come forth, naturally free of negative emotion. Sometimes the best method might be simple, to just look into one’s breathing as it comes and goes. One achieves a certain concentration that can still conceptual thoughts. Then, perhaps, one can see, as you have said, Fr. Laurence, that God is love and all human beings have a seed of that love–a seed of infinite compassion. This is what Buddhists call Higher Being. But yes, love is the most important factor to create a happy life.”

Carl, one of the conference organizers, had been sitting on his cushion about ten feet in front of Fr. Laurence and His Holiness. Now, he raised his hand and nodded to them. They each put their hands together and bowed from the waist to each other and then to all of us. They slowly got up from their cushions and turned around toward the Bodhi Tree where there was a path into the temple. There, they would spend ten minutes together in silent prayer. As was our custom with His Holiness, when he entered or left a room, everyone stood. My heart began to race with self-consciousness. Time to play the longer piece as the group waited for our leaders to return.

After breakfast this morning, Fr. Laurence and Carl had asked me to play here, while His Holiness and Fr. Laurence were gone. Carl explained, “You will play for ten or twenty minutes while the group meditates. After Fr. Laurence and His Holiness emerge from the temple, they’ll lead a discussion about the common ground and the distinctions between our two faiths.”

I moved my cushion to be more visible to the group and got out the score for Jinbo Sanya, an eight minute honkyoku. Now was my chance to practice the open-heartedness that His Holiness and Fr. Laurence had talked about, to practice my discipline, to concentrate and to love others through the music.

As Fr. Laurence and His Holiness disappeared behind the Bodhi Tree, people stood on their blankets to stretch. Remaining on my cushion, I slowly unwrapped the flute and hoped that the guards would not think it was a weapon.

Acutely aware that I was sitting beneath the sacred Bodhi Tree and that perhaps the eternal Buddha was especially present there, I bowed and then introduced myself to the group as they sat down again.

“Good morning. I am Robert Jonas from Boston, USA. Some of you have heard me play this instrument, the shakuhachi. This instrument comes out of the Buddhist tradition called “Blowing Zen,” and I play it as a Christian. In Blowing Zen, called Sui-Zen, the style of music is called honkyoku or Origin Music. Music from the Origin. I take it to be that place of silence and blessedness that is the source of our cosmos. Honkyoku is not so much about melody as it is a practice of deep listening, to draw the player and listener’s attention to the origin of all things. It’s good to play special attention to the silence between each note and breath. Maybe this between-place is what Buddhists called Emptiness and Jesus calls “the peace that passes understanding.”

I looked up to see hundreds of Tibetans outside the fences that surrounded us, trying to get a glimpse of the Dalai Lama. Perhaps some of them had been tortured by the Chinese. They knew that now their allegiance to the silence of the Buddha might mean execution. Jesus expressed God’s silence eloquently during the interrogation preceding his crucifixion. He said nothing. As I stood under the Bodhi tree, I was humbled by the bravery of the Tibetan people. But I could barely stand the suffering I saw on their faces.

Glancing at the Tibetan Rinpoches (teachers) and monks in the front rows, I hoped that they might feel inspired to realize that we Christians feel solidarity with them in their struggle to be free of Chinese domination. I continued, “I will play a piece called Jinbo Sanya, translated by my teacher as ‘Prayer for a Safe Birth.’ Some say that Jinbo Sanya emerged from the monasteries of Fuké monks who once wandered the villages with their begging bowls and flutes, stopping to play at those huts where a woman labored in imminent childbirth. Maybe other pieces were played by monks in this situation as well. But for me, this piece feels like giving birth.

“Perhaps you will hear that Jinbo Sanya begins slowly, contemplatively, like false labor. Soon, the contractions become heavier and heavier, requiring all one’s loving and aggressive concentration. Peace returns after the baby comes, and before the baby becomes a teenager.” I was nervous and a little self-conscious, so thankfully, everyone laughed with me.

“Jinbo Sanya is a metaphor. It reminds us that the journey to spiritual rebirth is sometimes very painful. And, much as we would like, there is no avoiding the painful contractions leading up to rebirth. We Christians say that there is no way around the cross.”

I looked into the eyes of the Lamas in the first row, smiled and added, “And we might say that the Tibetan people have been given a very big cross.” Again, thankfully, most listeners smiled with me. I could only hope that they were aware of my sincerity.

“In fact,” I continued. “While we don’t seek suffering, we feel that when we devote our lives to God’s love, suffering can become the doorway to true Christian enlightenment. The suffering of Good Friday is enfolded within the Resurrection and the Resurrection is hidden in every struggle. Here, in the Tibetan Buddhist community, our hope is that the Resurrection becomes real in the liberation of Tibet.”

I spread out the Jinbo Sanya score–written in Japanese katagana script–in front of me and glanced up to see that most people were sitting down. First I took a few deep breaths into the silence. Then I bowed, brought the shakuhachi to my lips and blew the first long, low-octave and calming note. Inhaling again, I smelled the dirt, the subtle, sweet aroma of the tree, the incense burning nearby, and the ever-present smog. I heard the cries of the vendors outside the temple grounds. As I blew the notes into the bamboo, tender memories drifted through my mind and heart. I saw myself in a three-some hug with Margaret and our son Sam, with my younger brother Steve who was struggling in a mid-life crisis, and two women of the Empty Bell community recently diagnosed with breast cancer. I saw myself playing baseball with Sam. I remembered His Holiness saying that thoughts and memories never cease, even for him. The discipline of meditation was not to be attached to the images. One shouldn’t struggle with thoughts, or try to reject them. Just let them be.

For a brief moment, as I blew, I took permission from my Christian faith, that these memories had come to me for a higher purpose. Perhaps, images of my loved ones were being given to me now so that they might be blessed through my breath, the bamboo, and this place. Perhaps this was intercessory prayer happening on its own, by grace.

The notes continued to come, easy and fluid as I remained concentrated on the proper fingering of each note. Occasionally, to stay focused, I let the phrase, “Just this, Just this,” be repeated silently within my blowing breath.

The notes seemed to blow themselves down the bamboo with loving-kindness toward my family and friends, and all the poor Tibetans who stood outside. I listened as if I was listening to someone else play, someone kinder, wiser and more loving than I was. His Holiness spoke about the value of spiritual places, and right now, it seemed true. I did feel the strength and clarity of the Bodhi tree within and between each breath.

Suddenly, when I was about halfway through the piece, I saw everyone getting up from their cushions. I realized with horror that Fr. Laurence and His Holiness were already walking up from behind me. If that was so, I was supposed to stand. But I felt completely involved in the birthing contractions of Jinbo Sanya, and I wasn’t done.

What could I do? Would the Dalai Lama think that I was being disrespectful if I didn’t get up? Here I was at a delicate moment of transformation in the music. The contractions had been building toward a resolution. This was more than a musical piece to me. The music was bringing us through the birth canal now! How could I abort the new life?

Everyone was standing as I heard footsteps behind me. I blew into the next note and relaxed. Maybe I should stay seated. But was I taking myself and Jinbo Sanya too seriously? After all, it was just a piece of music and this was His Holiness, a living incarnation of Chenresig, the Buddha of Compassion. What would Buddha do? What would Jesus do? As I blew I was analyzing the situation, looking for guidance. Had any teacher ever given me a tip about what you do in a situation like this? Maybe I should have stopped playing, stood up and bowed out of respect. Would Christians carry on with their regular morning prayer if Jesus had walked into the room?

I felt the muscles in my stomach and back tighten. I saw no easy way out. Like the Zen koan, “Where do you go from the top of a hundred foot pole?” Ya, where? Either I offended His Holiness, or the honkyoku tradition of Jinbo Sanya. Tension came into my shoulders as my face reddened. I faltered on a note.

With each new breath, I thought, “I’ve got to keep playing, one note at a time”. Then as I remembered the Dalai Lama’s smiling face and his ready humor, the tension drained away. Inwardly, I smiled as I realized that His Holiness would probably handle it. He’d been through many formal situations like this. He knew how to go with the flow.

I was about three-quarters of the way through Jinbo Sanya when I saw out of the corner of my eye that His Holiness and Fr. Laurence were bending down to sit on their cushions which were next to mine. As they began to sit, everyone else followed suit. Still, I had some hope that everyone was actually listening to my musical prayer and feeling inspired. It took about one second for this thought to go through my consciousness–that when I was through, Fr. Laurence would say out loud, “How wonderful. What a beautiful piece to hear at this moment, beneath the Bodhi Tree. And what a blessing to have Robert with us!” And the Dalai Lama would also reach across to shake hands with me, thank me, and ask me to accompany him around the world and to play honkyoku wherever he went!

Somehow, I maintained my concentration, even as another heavy one-second thought come through. What if His Holiness and Fr. Laurence were embarrassed by my playing? They’d heard every kind of sacred music on this planet by now, and they thought that I stink. They were wondering how I got invited to do this and they wanted to get on with the retreat.

My mind jumped around like a tree full of monkeys, but fortunately, my breathing and blowing continued like a big, automatic bellows. Deep breath in, long, blowing breath out. Deep breath in, long, blowing breath out. One note after another. My fingers remembered what to do.

But even as I entered the final section of the piece, I noticed a sharp emotion in my chest. It was anger! I was blowing outrage into the flute because the Dalai Lama was ignoring me, bending forward on his cushion and whispering to his aides. He was talking, as if he didn’t appreciate the profundity of this moment. Now I was offended. In Japan, one wouldn’t speak during honkyoku. An ideal image of formal Sui-Zen performances popped into my mind. Ideally, His Holiness and Fr. Laurence would have stopped as they came back from prayer, and stood behind me, waiting respectfully as I finished.

As Laurence settled onto his cushion, I suddenly realized that my little meditation cushion slightly overlapped his large zabuton. Since I didn’t know the whole of Jinbo Sanya by heart, I had spread the score out in front of me, part of it resting on a corner of Fr. Laurence’s zabuton. And now, as I entered into the last lines of the piece, Laurence sat down and pushed my music aside. Luckily, I was blowing a note that made my right hand superfluous. I quickly grabbed the score, slid it across the dirt to the left, shifted my body away from Laurence and continued to play. I couldn’t believe Fr. Laurence’s rudeness. Did he think that his words were more important than my music? But then, maybe I was being rude by sitting here, invading his cushion-space, and continuing to play. Everyone had come here to listen to Fr. Laurence and His Holiness, not to me. Who do I think I was? With the thought came a surge of shame in the back of my neck and in my face. Was my music more important than this incarnation of Buddha or this important Benedictine monk?

As I blew one long note, I glanced ahead and realized that I might have two minutes more to play. The Dalai Lama was whispering to his Lamas and Laurence was silent. I imagined that he was impatient to resume the dialogue. But I still wanted to convey the essence of Jinbo Sanya.

Now, I saw that I could go to the last line of the piece with some grace, so I did. I was determined not to let my chaotic thoughts and emotions interfere with my sincere wish to blow each note beautifully and simply, with full attention. After all these heavy contractions, just a couple more pushes and the baby would be out. Breath in, blow out. Silence. Breath in, blow out. Silence. Breath in, blow out. Silence. And that was all. Jinbo Sanya was over. The labor was done. He was here. I bowed.

I was pleased when Fr. Laurence did not begin talking immediately after the last note. In these five seconds of silence I glanced up to see almost everyone sitting still with their eyes closed. Perhaps they did receive, in their hearts, the blessing of Jinbo Sanya. I did want each of them to have a safe birth in their souls. While it seemed that many people had appreciated this shakuhachi offering, I was ashamed that it mattered to me. Why did it matter?

As Fr. Laurence resumed the dialogue between him and His Holiness, I was not listening. Instead, I thought about what just happened. I smiled and relaxed when I realized that I was feeling shame about feeling shame. Once again, I felt lucky to have learned something from years of meditation. Negative thoughts and feelings come and go. Just let them do what they do. Don’t get to involved in them. Shame comes and goes. Shame about shame comes and goes. I felt the happiness that comes with detachment.

Still, I did notice that when Fr. Laurence began speaking after my playing, he didn’t say anything about it. What did he think? Did he like it? Was he really impatient or even angry with me? During this first of three mornings of meditation and dialogue between Fr. Laurence and the Dalai Lama there was no way to test the reality of the interior soap opera that I’d experienced. Given the rules about not approaching the Dalai Lama, I couldn’t check out what he had thought about Jinbo Sanya. I could only do what good meditators do, let it go. When Fr. Laurence and His Holiness finished speaking our group–all having sat on the dirt that surrounds the Stupa–got up and were directed to stand in, and to approach His Holiness, one by one, to receive a sacred white scarf. I joined the line and when I came face to face with the Dalai Lama, he hung a scarf around my neck and said, “Thank you for playing the flute.”

At the end of a long morning of meditation and dialogue, as our group walked slowly out of the temple grounds, I pondered the lessons of my brief Bodhi Tree recital. I saw how tangled up in self-consciousness I could become. I saw it vividly like a movie I’d watched over and over all my life. Who cares what people think? I felt a curious mix of pain and relief in my chest. I didn’t care what people thought about me. But I did. My narcissism was like a snake coiled about me, its head and tail out of reach.

So, it was both. I cared and I didn’t care. In my pain, I longed to find a balance. If my attention was too much on others, I lost touch with myself. On the other hand, if I was too self-conscious and self-absorbed, I was not in touch with others.

Up ahead I saw the Dalai Lama’s balding head sway back and forth as he slowly walked ahead of the crowd, stopping to bow to people along the path to the exit. Could I be aware of him while simultaneously staying at home inside myself? My life was at stake here. I needed some reminder, a spiritual tool for the job. Watching him, I found myself whispering the phrase “I don’t care what you think”.

At first I felt that I was being cruel to him. But he had no idea what I was thinking. He didn’t care what I thought of him. I felt the power of the idea like an ancient, sacred mantra: “I don’t care what you think.” Be free of what others–even very important others–think. I imagined that Jesus carried this mantra, especially when the religious authorities of his day lashed out at him. Each time I said I didn’t care, I felt stronger and more at ease, and an even deeper level of care seemed to well up within me.

Now a memory of my grandmother, Leona Radenz, came to mind. Grandma was a severe but loving German woman. As she wiped catsup from my face she scolded me, “What will people think?” When I was small, she told me to make sure that I put new underwear on every morning—they were there in the antique wooden chest of drawers near my feather bed, the top drawer, just beneath the white doilies, all freshly washed and folded—in case I had to go to the doctor’s or the hospital today. You didn’t want them to see your dirty underwear. What would they think?

My heart lingered in Grandma’s vicinity as walked the dusty road in Bodh Gaya. Grandma was German Lutheran. Orderliness, cleanliness and Godliness. Every Sunday she went to her German-speaking Lutheran church. Through her I received the Protestant energies of Martin Luther, a Roman Catholic friar who bravely stood up to oppose His (Christian) Holiness, the Pope. Luther declared, “Here I stand!” He was totally committed to his Christian life and he had pledged allegiance to the Pope. But now he had come to this moment of truth. Where would he stand? Did he care what the Pope thought of him? He must have let go of that. But relationships can be complicate. I did care about Grandma, and I did care that she loved me, and took me and my siblings in when my parents became unreliable. She taught me to pray, Ich bin Klein mein hertz ist rein, Darf niemand drin wohnen als Jesus allein (I am small, my heart is pure; no one lives in my heart, but Jesus alone).

Luther, of course, didn’t feel like he was alone in the spiritual struggle. His teacher and Lord, Jesus, also knew about truths that transcend the importance of friends, family and authorities. Some days Jesus was praised, some days he was spat upon and one day he was executed for his religious beliefs. If he had listened only to other people’s opinions, he might have lived longer, but he would have been a basket case. He wouldn’t have been true to himself.

Jesus and Luther both had faith in themselves, and in God. God was the source of their courage. They must have come to this—I don’t care what anyone thinks. They didn’t care because they were rooted in the unconditional love of God. Their love for others was stronger than their opinions about them or their fear of them. Wretched or glorified, Jesus and Luther walked in a Light that transcended opinion. It seemed ironic that here, in the presence of two spiritual leaders who exemplified the ultimate value of caring, I didn’t care. What kind of caring doesn’t care?

Walking out of the Stupa grounds I thought about how both Christians and Buddhists had struggled with ways to be aware of others’ opinions, but not attached to them. Both traditions called attention to the practice of detachment, a way of being present to what is happening, while not being overwhelmed and carried away. Third and Fourth century Christian monks in the Middle East named it apatheia, a state of perfect equanimity in the midst of the extremes of experience—suffering and joy, beauty and ugliness, pleasure and pain, life and death. I assume that these monks still had experiences of fear, low self-confidence, guilt and shame, of course. But now, they taught that one could not react to them in a primitive, instinctual and self-centered way. In apatheia, I might care what the Dalai Lama thought about me, but I saw that it was just a thought and that caring-in-God is more important to me than the fearful “caring” that fills the space of our ordinary monkey minds. “Here I stand.” Luther’s declaration, suddenly made sense to me. Who would think that I’d feel closer to Martin Luther by playing Sui-Zen under the Bodhi Tree with the Dalai Lama?

As we our procession made the final ascent up the stairs of the temple past the crowds of Tibetans, I was repeating my sacred mantra when I sensed someone beside me. It was Connie, the Baptist minister. My roommate, John, had introduced me to her that morning after breakfast. I had learned that her husband was a Baptist minister. They taught Bible courses in Thailand. I turned to see her smiling at me kindly. I smiled back.

We walked side by side for twenty feet. Then she said, “Thanks so much for your shakuhachi, and for your words about giving birth. It was so wonderful to hear someone acknowledge the value of women’s experience here, under the Bodhi tree.”

“Whoa,” I said smiling, “I was just thinking about male warrior energy, the willfullness to cut through illusion for the sake of some truth, not caring what people think. But you’re right. Giving birth is warriorship too, isn’t it?”

“Sure,” Connie said, “I remember howling with the contractions. It was a big deal for me. I broke through an old, habitual nice girl image. It was liberating.”

“I’m glad that you were reminded of that. I’ve been at the birth of my children, and I hoped that I was putting that kind of visceral energy into Jinbo Sanya. Playing it was like swinging a sword through an army of images–‘Me, not me. Me, not me.’ Jeez, I had to be ferocious to get through it.”

“Oh ya,” Connie replied. “I got it.”

“You did, you do?”

“Sure. See, I think that a Christian’s goal ought to be finding one’s true identity. You battle through a thicket of me’s and not me’s with the sword of the Holy Spirit and one day, before you realize it, you’ve lost yourself in Christ and you can’t get back. That’s Christian Enlightenment, Christ’s nativity.”

On the bus back to our rooms, my mind flashed ahead to next month when we would celebrate Christmas, the incarnation of God in Christ. And I thought of my dear Meister Eckhart, the medieval Dominican friar, who said that we are all mothers of God and that the celebration of Christmas is useless unless that holy birth happens in each one of us. (Raymond Bernard Blakney, tr. & ed. Meister Eckhart: A Modern Translation. New York: Harper & Bros., 1941, The Sermon: “This is Meister Eckhart from whom God hid nothing”, pp. 95 ff.) I prayed for that holy birth in myself and in all people, including the suffering people of Tibet. And I prayed that the Sui-Zen tradition would continue to express this labor of love to people of other faiths and cultures.

Two days later, at our last afternoon session in the meditation hall at the Root Institute, His Holiness and Fr. Laurence had been talking about spiritual emptiness. The Dalai Lama had said that Buddhists don’t believe that the cosmos has a beginning. “We speak about beginingless time. Time stretches in infinite directions. But others might say, ‘First emptiness, then Creation. Emptiness is fundamental. Without emptiness, nothing can exist. Everything comes from emptiness.”

“That’s true for us as well,” Fr. Laurence replied. “For us, emptiness is the Father, who Jesus called Abba. Abba is the limitless source in the Trinity. The manifestation or incarnation of that limitlessness in human form is Jesus. The Creation happened and the Incarnation happened because God emptied himself into the Trinity and into Creation. In Christian scripture it is said that Christ emptied himself, just as God does eternally. We use the word kenosis in Greek.”

“This is very interesting,” said His Holiness as he leaned toward his translator and had a short conversation with him. Then he turned back to Laurence. “Perhaps your Trinity has some parallels with our Buddhist Trikaya, with Dharmakaya, Sambogakaya and Nirmanikaya. Perhaps we have something similar, where Dharmakaya is a manifestation of the Unmanifest. But we must be careful not to confuse our two beliefs. There are also differences.”

“Your Holiness,” Fr. Laurence said, smiling, “I can see we have many fruitful avenues for future discussion. But let us pause right here, for today.”

This was my sign. I sat on a chair on the aisle so that I could see both Fr. Laurence and His Holiness clearly. Now as we entered into a twenty-minute meditation, I was to play a short piece. I’d selected DaiWa Gaku for this, my last musical contribution. I wanted to play it from the ultimate source, from the Dharmakaya, from Abba.

I sat up straight, raised the shakuhachi up horizontally and bowed to our leaders. They were both looking at me, expressionless as they each bowed slightly toward me. I raised the shakuhachi to my lips for the first long note. I was acutely aware of a hot, pulsing toe on my left foot. Last night I had noticed a red, inflamed area around the toenail. A few days before, my naked, sandaled foot had slipped sideways in a pile of cow dung at the entrance to a Hindu temple. Had I become infected? I had lain awake in bed, wondering if I might die here in India. Now, the sore toe seemed directly tied to a fear of death, or at least, a respect for its imminent presence. As was my habit in situations like this, I directed the fear into my breath as I blew into the shakuhachi.

As I completed the delicate, dwindling tone of the first note I glanced up to see His Holiness and the Fr. Laurence meditating in silence. Stay focused, I told myself as I took an in-breath. My left toe continued to hurt badly, reminding me of the foot infection I had had the previous year. When I had finally seen my doctor in Cambridge, he had said “This is serious” and immediately sent me from the clinic to Mount Auburn Hospital where I was put on heavy-duty IV antibiotics. Then I was taken home–with nursing care–to stay in bed for five days hooked up to the IV. Later the doctor told me that he had been worried. I had contracted a resistant strain of bacteria that could have spread up my leg. It could have killed me, he said.

So, here I was, near death, blowing one note at a time down the shakuhachi under the sacred Bodhi Tree as the Dalai Lama listened. Everyone sat on their cushions silently with eyes closed while my inner drama played itself out. I was aware of smiling slightly, just enough to maintain the embouchure of my lips. What a way to go, to die in Bodh Gaya. Sure, I was practicing Sui-Zen, letting go of my thoughts with each breath, but who wouldn’t, at such a moment, remember Fr. Thomas Merton who was accidentally electrocuted here in Asia just after attending talks with the same Dalai Lama? In my mind’s eye, I saw a little obit in the Boston Globe, “Dead in Asia, like Merton,” or “How beautiful. He died playing the shakuhachi for the Dalai Lama.” The fear was moving in my breath and into the ambience of the note. I missed my family and wanted to return to them.

One note at a time. Thinking. Why had I come here? Why did I go to the temple in sandals? Last night I had only slept three hours, obsessively retracing my steps to that temple in Varanasi. My new friend John and I had gone into the narrow, labyrinthine streets near the Ganga River. We picked up one of the ever-present young guides who led us as we wound our way past cows, beggars, shopkeepers and local inhabitants to the Golden Temple, one of the most holy Hindu sites. We had heard that this was a good place to go for a blessing from a Hindu priest. Non-Hindus could not go into the temple itself, but we could be received in one of the outer altar areas and receive a special blessing. I wondered if there really was something special about a “special” blessing.

John and I found the priest in the walkway, and he instructed us to take off our sandals. I was reluctant because the stone walkway was slippery with the excrement of cows, dogs, birds and humans. I had already slipped. But I did it. Standing barefoot at his altar, we ended up paying 100 rupies each for a blessing from the priest. He insisted that his blessings were really worth twice that much, and if I were a good person I would offer the gods another 100. I refused, so of course I worried that this priest was getting back at me by cursing me with a toe infection.

Back to the breath, I was playing Daiwa Gaku. Feeling the strength of my will to live, I blew into death, and through it. I let myself have faith that within me, the breath of life was blowing right through that vast, dark, impenetrable wall between life and death. Each breath seemed a protest and a blessing, and a grant of mercy to those who faced death or who had already died. I felt close to tears as I blew, and my heart seemed bursting with love.

Somewhere toward the end of Daiwa Gaku, I peeked up to see the Dalai Lama sitting with his eyes closed. He looked different, radiant. Now as I breathed into one of the last few notes, I felt his radiance come into me. My cheeks grew warm. I was sure they were glowing red with joy. His Holiness turned slightly toward me, put two hands together in prayer with the fingertips pointed toward me, and then brought his hands to his forehead as he listened to the final notes. I imagined that he had entered into another depth of compassion in his prayer. The hairs on the back of my neck stood. I felt that our prayers, the prayers of Buddha and Jesus overlapping within us and between us.

It seemed that the final strong, flowing notes of Daiwa Gaku were going out from both of us, a river of blessing from both of us, expressed through the shakuhachi and the body of His Holiness. Our hearts were one, as if we were sitting at the bedside of a dying friend. All three of us were receiving and giving something eternal, a complete merciful blessing. The last note that emerged from the bamboo wasn’t mine. It was the sound of the Dalai Lama’s radiance, spreading out to all the suffering people around Bodh Gaya, in Tibet, and in the world. As I let the last breath go, the Dalai Lama’s image shimmered through my tear-filled eyes. Later, I wondered if my sore toe had anchored me in the vicinity of death, so that I would be forced to be more realistic about my mortal situation, honest about the great suffering that surrounded us, and true to my highest aspiration, to be in God when I die.

For the rest of the afternoon I glowed with peace and I felt the Dalai Lama’s courage and compassion in my reddened cheeks. But after dinner a more sober level of reflection began. What if, in that moment when he raised his hands to his forehead, His Holiness was praying, “Please make this ugly music stop!” I would never know. But did it matter what he thought?

Now, I remembered the Dalai Lama’s words when he placed the white scarf around my neck, “Thank you for playing the beautiful flute.” I had been stunned and gratified. And I suddenly realized that all that inner struggle, wondering what Fr. Laurence and the Dalai Lama thought about me and my music, and the shame that came with it was all about me. Just me. It was all about coming to terms with myself–facing my negative, critical inner voices and facing my own death. With a smile I remembered what my mentor and friend, Henri Nouwen, once said in a sermon. He had been talking about the small identities that we settle for and one of them was an identity that is completely circumscribed with what others think about us. “But,” he said with a chuckle, “when you’re dead, you’re dead. People don’t talk about you anymore and you don’t care what people think anymore.” So, why not be free now, while we’re alive and can enjoy it? As ancient Buddhists and Christians said, “Die before you die.”

Suddenly I saw that this was exactly what one is invited to do under the Bodhi tree, the place where Siddhartha Buddha finally saw through the infinite levels of self-talk and illusion within himself. This is why I had come here. No one could have told me ahead of time that this or that was “supposed” to happen here. If it were planned, it wouldn’t have happened. Maybe there was something to what His Holiness was saying, that there are special places on this earth, where, if you are open, blessings and healings may come.

As our group walked back to the Root Institute I felt some Buddhistic detachment about the Dalai Lama’s opinion of me. But I had to laugh at the circuitous and sometimes tortured path by which I had come to it. Perhaps we all receive occasional glimpses of enlightenment, unconditional love and true freedom. I suppose that some people might receive these visions by pure grace, out of the blue. But in this instance, by the time I received that rare peek into God’s free Spirit and my true self, I had been exhausted and bruised by the fear, self-doubt and insecurity that circulated in every breath that I blew through the shakuhachi. I hoped that this would get easier, but I also suspected that my suffering, fear and resistance would continue to be rungs on the ladder that I was destined to climb, or descend.

© Robert A. Jonas, 2006, 2023 (reprint by written permission only)